7th century

Asuka Bijin Cave Paintings (c600-699) Anonymous Koreaboo person

Tenjukoku Shūchō Mandala celebrating Prince Shotoku (622[1944]) Chuguji Temple, Tokyodo

Empress Suiko (593-628[1726,2015]) Tosa Mitsuyoshi, Anonymous

Tang Influenced Courtwear (690-705) Anonymous

8th century

Empress Komyo (701-760[1897]) Kanzan Shimomura

Empress Koken (718-770[1799-1899]) Sumiyoshi Hiroyasu

Fujiwara no Toyonari (720–765[1908]) Kokusho Kankōkai

._(33%2C7x204%2C8)_Beijing_Palace_Museum.jpg)

Lady with Servants (799) Zhou Fang

_Liaoning_Provincial_Museum%2C_Shenyang..jpg)

Court Ladies adorning their hair with Flowers (c799) Zhou Fang

9th century

Fujiwara no Tsunetsugu (838[1903]) Anonymous

10th century

.jpg)

Yang Guifei (c907) Liao Wall Tombs of Pao Mountain

12th century

Genji E-maki (c1130[1937]) Kyoto Painter Person

Kunai Kyo the Poet (c1183-1198[1660]) Kiyohara Kano Yukinobu

Genji drooling (d.1191[c1617]) Tosa Mitsuoki

Nara reconstruction clothing (2005) Feitclub

16th century

Yamato-E (c1517) Tosa Mitsunobu

.jpg)

Momoyama Nushime-Shibori Sample (c.1568) Anonymous

Iapon from the Boxer Codex (1590) Anonymous Continental Author

Yoko Kasuri (c.1596-1615 [2018] CC1.0) Honolulu Museum of Art

17th century

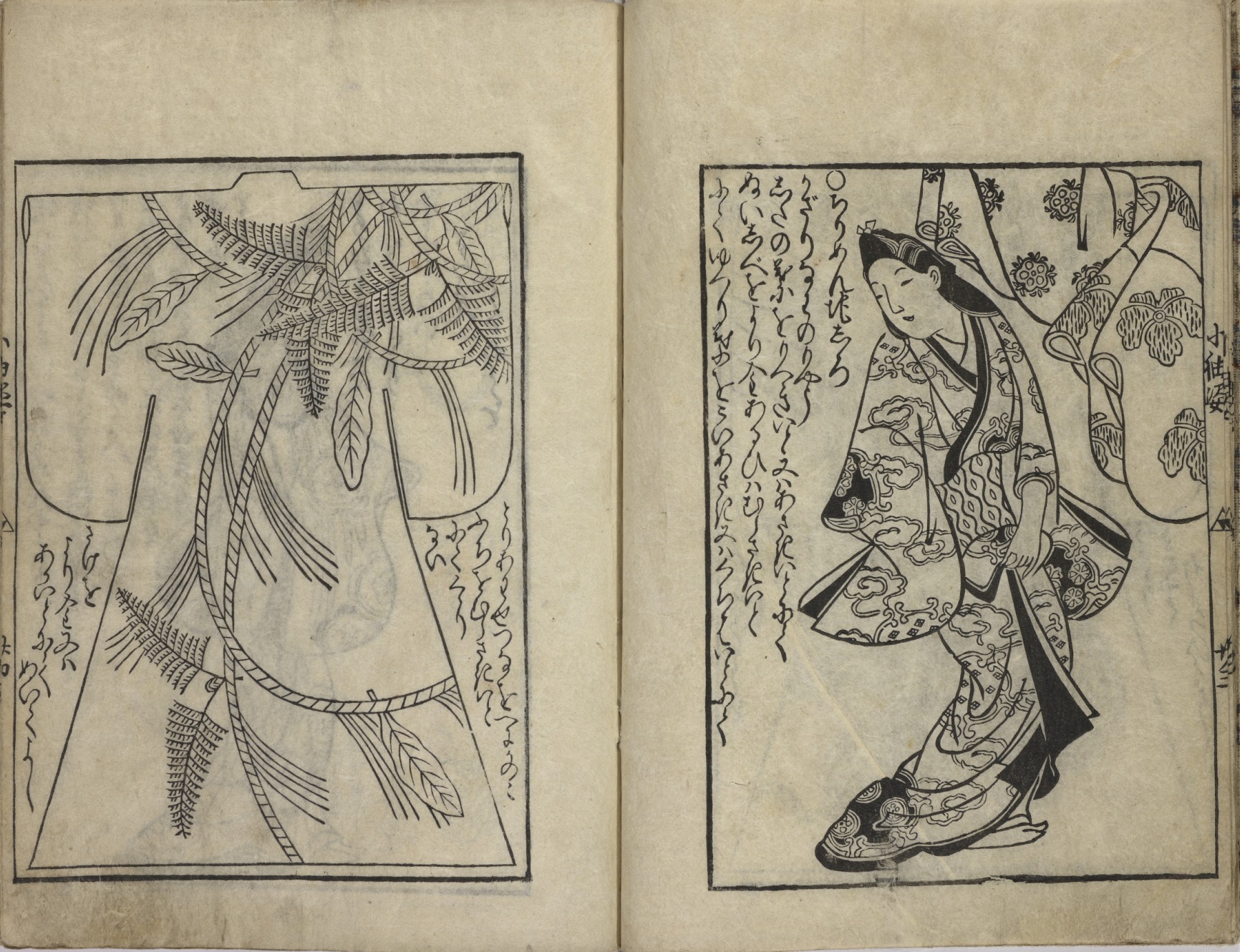

Tales of Ise (1608) Soan Yoshida

_MET_DT1618.jpg) Bamboo Group Era Tagasode (c.1615) Anonymous

Bamboo Group Era Tagasode (c.1615) Anonymous

O-Kuni performing Kabuki Byobu (c.1603-1613) Hasegawa, Kyoto National Museum

Outdoor Amusements (1615) Suntory

Hikone Byobu (c.1624) Unknown

The Four Earthly Pleasures in Kosode (c.1624-1650) Iwasa Matabei

Bamboo / Wood Stand Tagasode Byobu (c.1625) Anonymous

Fan Dancer Byobu (1630-1660) Suntory Museum

Shikomi-E (c1630-1660) Anonymous

Three Dancing Samurai (c1649) Iwasa Katsushige

Iwasa Portrait (1650) Iwasa Matabei

Kambun dual tone Kosode (c.1660) Unknown

Onna Shorei Shuu Tagasode (1660) Anonymous, NYPL

Shikomi-e (c1660-1670) Unknown

Seated Bijinga (c1661) Iwasa School

Grand Shimabara Courtesan (c.1661-1673) Yoshi

Lovers Caught Surprised (c.1665-1669) Kambun Master School

Dress and Table Manners from Rules of Etiquette for Women (1666) Yamada Ichirobei

Wakashu Dancer (c.1670) Hishikawa Moronobu

Untitled (c.1670-1673) Iwasa Katsushige

Beauty Looking Back (c1672) Hishikawa Moronobu

Two Beauties (c1672-94) Hishikawa Moronobu

India Coromandel or Sarasa Fabric Sample (c1675) Anonymous

Tan-E (c1676) Sugimura Jihei

Kosode Designs (1677) Hishikawa Moronobu

Lovers Visit (c.1680) Tamura Suio

Genroku Kosode Sample Design (c.1680)

Beauty (est1680) Sugimura Jihei school

Hinagata Bon and Wakashu (1682) Hishikawa Moronobu

Wakashu Shunga-e (1685) Sugimura Jihei

100 Japanese Women (c1685-1694) Hishikawa Moronobu

Wakashu Shunga-e (1685) Sugimura Jihei

Wakashu Shunga-e (1685) Sugimura Jihei

Dally Couple Wakashu Shunga-e (1685) Sugimura Jihei

Furisode of Amorous Women (1686) Ihara Saikaku, Yoshida Hanbei

Yonosuke with Telescope from The Life of an Amorous Woman (1686) Ihara Saikaku

Womens Yuugao Genji Kosode Designs (1687) Yoshida Hanbei

Korean Chrysanthemum Pattern (1687) Yoshida Hanbei

Carp Waterfall Pattern (Joyo kinmo zui; 1687) Yoshida Hanbei

A Kyoto theater, where a youthful actor is admired for his natural beauty (1687) Ihara Saikaku

Bottom Heavy Genroku Spatial Arrangement (c.1680) Anonymous

GKTC or Genroku Chonin Kosode Fashion (c.1688) Unknown

Beni Kosodes, Kana and Shibori GKTC (c.1688) Unknown

Kimono Designs (1688) Yezoshiya Hachiyemon

Shunga Trio (c.1690-1740) Miyagawa Chosun

Indigo Satin Shibori Chrysanthemum Kosode (c1690) Tokyo National Museum

Man in Silk Kimono (1696) Michiel van Musscher

Tan-E (1698) Torii Kiyonobu I

18th century

Japanese Stencil Sarasa (c.1700) Japanese person

Yuzen influenced Kosode (c1700) Ishikawa Prefectural Musuem of T. Arts & Crafts

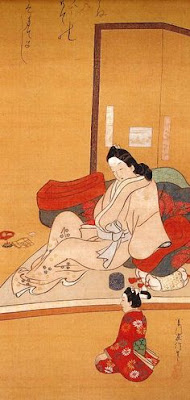

Reclining Courtesan and attendant (c1704, PD) Hasegawa Eishun

Beauty in a Black Kimono (1710-1720, PD) Torii Kiyonobu I

Shunga-e; or A spot of wrestling is good for the soul says the 6th Dalai Lama (c.1711) Unknown

Client, Kagema and Asobi (c1716) Nishikawa Sukenobu

Courtesan with looped hair (c1716) Kaigetsudo Doshin

Yuujowho (1717) Nakamura Senya

Beni-E (1720) Torri Kiyonobu I

High Yuujo and attendant (1723) Nishikawa Sukenobu

Urushi-E (c.1728, PD) Okumura Toshinobu

Benizuri-E (c.1744, PD) Ishikawa Toyonobu

Walking Courtesan Kakemono (c1748, PD) Nishikawa Sukenobu, British Museum

Woman in Florals (c1765, PD) Suzuki Harunobu

Nishiki-E (1765-1770, PD) Suzuki Harunobu

Hashira-E (c1772, PD) Toensai Kanshi, British Museum

Woman in Black Kimono (1783) Katsukawa Shunsho

Courtesans of the Tamaya house panel section (c1785, PD) Utagawa Toyoharu, British Museum

Fresh Model Designs (c1789, PD) Takikawa School, British Museum

Yuujo applies facecake (1795) Kitagawa Utamaro

Karamonoya store (1798) Niwa Tohkei

Kara-ori Embroidery Robe (c1799) Smithsonian Design Museum

19th century

Young woman in Boat (1802, PD) Utagawa Toyokuni I

Beauties playing Hanetsuki (1805) Utagawa Toyokuni I

Starfrost Contemporary Manners (1820, PD) Utagawa Kunisada

Kamban Asanoha Ukiyo-e (1835) Utagawa Kunisada

The Old Man (c1843) Hokusai Katsushika

Terakoya (1844) Issunshi Hanasato

Sashiko-style Kimono (c1850) Anonymous

Beni Kimono (1850) Meteor Museum

Wakare ga Iyaso (1859, PD) Utagawa Kunisada

Sankin Kotai Procession (1861[1904,2010]) 投稿者がファイル作成

Morgan Le Fay (1864) Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys

The Beloved (1865) Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Girls Portrait (1868) George Price Boyce

Traditional Padded Oshi-E (c1868-1912) Sekka, Khalili Collection

Geiko (c1870) Anonymous

Ellen Terry in Kimono (1874) Ellen Terry

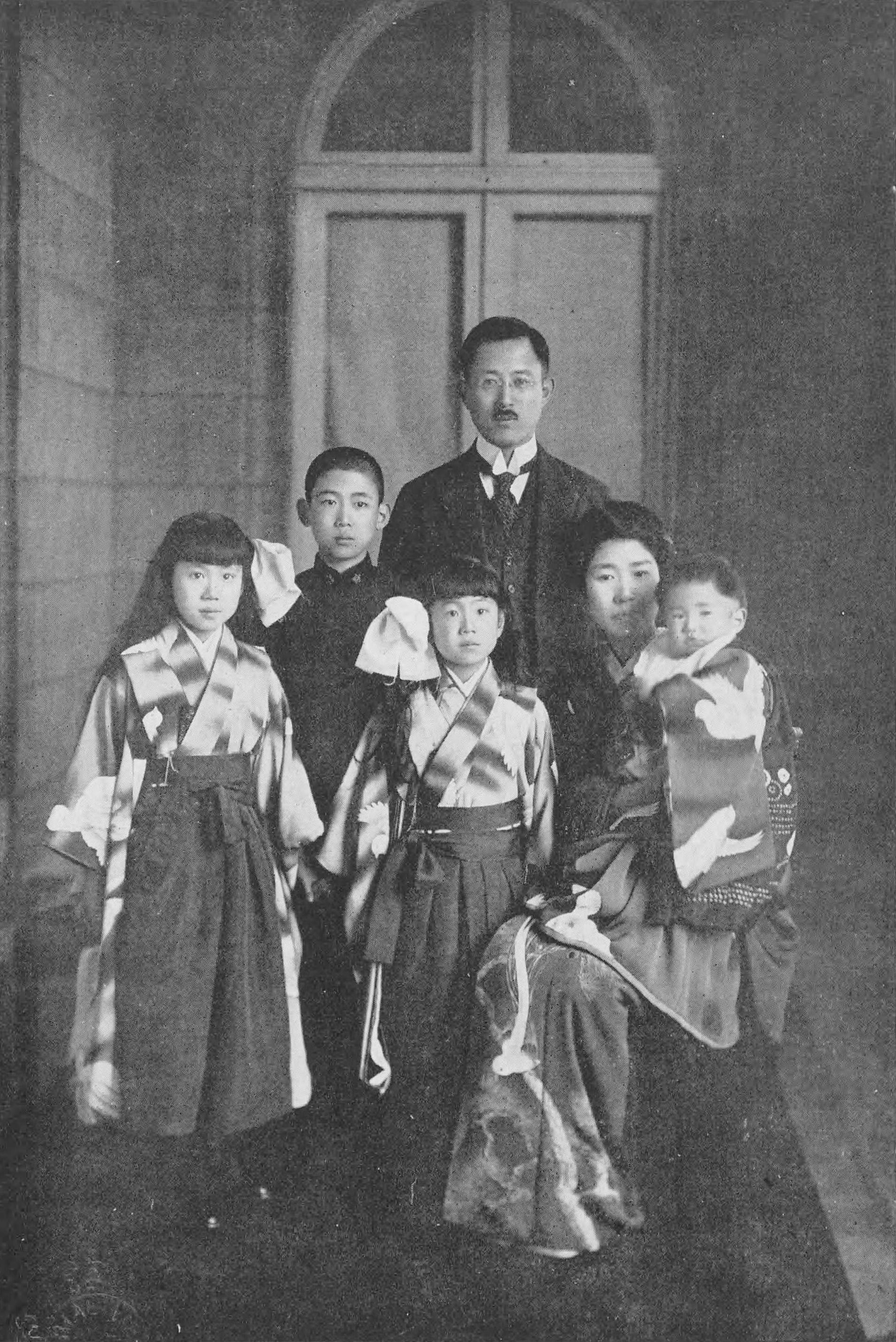

The Ootuuki Family (1874) 江戸ラー

Repurposed Kimono Day Dress (1874-76) Misses Turner Court Dress

Carp Kimono (1876) The Meteor Musuem found a pole!

Liberty Catalogue Advertisement (1880) Libertys Depato

Osono attacks Rokusuke (1881, PD) Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

The Green Kimono (c1882, PD) Frans Verhas

Three Little Maids from School (1885) Gilbert and Sullivan & Strobridge Litho. Co

Susanoo rescues Kushinada Hime from the dragon (1886) Toyohara Chikanobu

Hanetsuki (c1890[2016]) Kusakabe Kimbei, Monash

Contemporary Beauties (1890) Yoshu Chikanobu

Contes Japonaises (1893, PD) Félix Oudart

A Tea ceremony (1896) Mizuno Takeshita

Tricora Corset Advert (1899, PD) Boston Public Library

20th century

Metallic thread, Plain weave Yoko (weft) Kasuri (c.1900-1949[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Musuem of Art

Womens' Tate Kimono (c.1900-1939[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Musuem of Art

Darling of the Gods Theatre Programme (1903) Yoshio Markino

Anglo-Japanese Alliance Postcard (1905, CC4.0/PD) 三越百貨店

Plain weave Meisen (c.1907-1949[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Museum of Art

Ota Hisa or Hanako (1908, PD) Sport & Salon

Spanish Woman in Kimono (c190[8], PD) Gustave Gillman

Woman in a Kimono (1910, PD) Walter Crane

Woman in kimono (1910, PD) Julian Fałat

Plain weave Tate (warp) Kasuri (c1912-1949[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Museum of Art

The Setsuko Family (1912) Anonymous

Plain/Crepe weave Meisen (c.1912-1939[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Museum of Art

Kanto Plain weave Meisen (c1912-1939[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Musuem of Art

Fish Crepe weave Meisen (c.1912-1949[2018], CC1.0) Honolulu Musuem of Art

Geesje Kwak in Japanse kimono voor kamerscherm (c1913) Leiden Universitat

Kimono Girl (1914) Elstner Hilton

Princess Yasuko of Fushimi (1917, PD) Wikimedia

Takahashi Korekiyo with his Family in the Garden (1920) 婦人画報

Prince Kitashirakawa Naruhisa and his Family (1921, PD)

Kane Tanaka (c1923, CC1.0) Molly887956321

Moga (c1925) Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Preservation

Machine Made Meisen (c1926) Khalili Collection

Mirrored Hem (c1929) Meteor Musuem

Uchikake (c1930) Khalili Collection

Princess Kuniko of Kuni (c1936, PD)

A young women in a Furisode with a Chu Obi (1936, PD) Kawakatsu

What did the lady forget? (1937, PD) Shochiku, Sumiko Kurishima, Mitsuko Yoshikawa, Chōko Iida

Kawakami Sadayakko (c1937-1945) Anonymous

Battleship Meisen Haori (c.1938) Unknown

Schoolmarm at graduation ceremony (1953, PD) Meomeo15

Kimono Coats (1956) Shimbun

Women in Kimono (1956) 投稿者によるスキャン

Kimono in 1957 (1957) 投稿者によるスキャン

Les Brainards Grove Restaurant in Seattle (1963) Anonymous Statesian

Kappou-Gi (1969, CC4.0) Meomeo15

E-gasuri (c.1999[2013], CC3.0) Chris Hazzard

21st century

Furisode (2003) Lukacs

Tokyo Japan (2006, CC2.0) Dennis Keller

Kimono Girls in Kyoto (2008, CC2.0) Rumpleteaser on Flickr

Kimono Hime Fanzine (2009) Flickr/Kimono-Hime

Maiko serving Tea (2011) Nils Barth

Dori Style Michiyuki and Geta Kitsuke (2016) Tokyofashion.com

Dori Style Kitsuke (2016) Tokyofashion.com

Kimono Hime Street Style (2019) Tokyofashion.com

_Liaoning_Provincial_Museum%2C_Shenyang..jpg)

.jpg)

._(33%2C7x204%2C8)_Beijing_Palace_Museum.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_MET_DT1618.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_with_Cherry_Blossoms_and_Cypress_Fence_MET_1980_222.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(BM_1979%2C0305%2C0.70.2_11).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(BM_1907%2C0531%2C0.66_1).jpg)

_(BM_1942%2C0124%2C0.15_1).jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

_with_Carp%2C_Water_Lilies%2C_and_Morning_Glories.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)