This patternseries I would like to try something a little different, and discuss the process behind the revival of the pattern tsujigahana, by its revivalist, Itchiku Kubota (1917-2003) in 1937. Itchiku Kubota was the artisan or Komin who was behind the work of recreating the arguably lost art of creating Tsujigahana ( 辻が花 | Flowers at the Crossroad ), which became his lifes work.[1] Kubota was a great crasftman outside of this feat, but his work and what inspired I thought might be of interest to people into what motivates people to preserve, relish and continue creating these 'traditional' crafts.

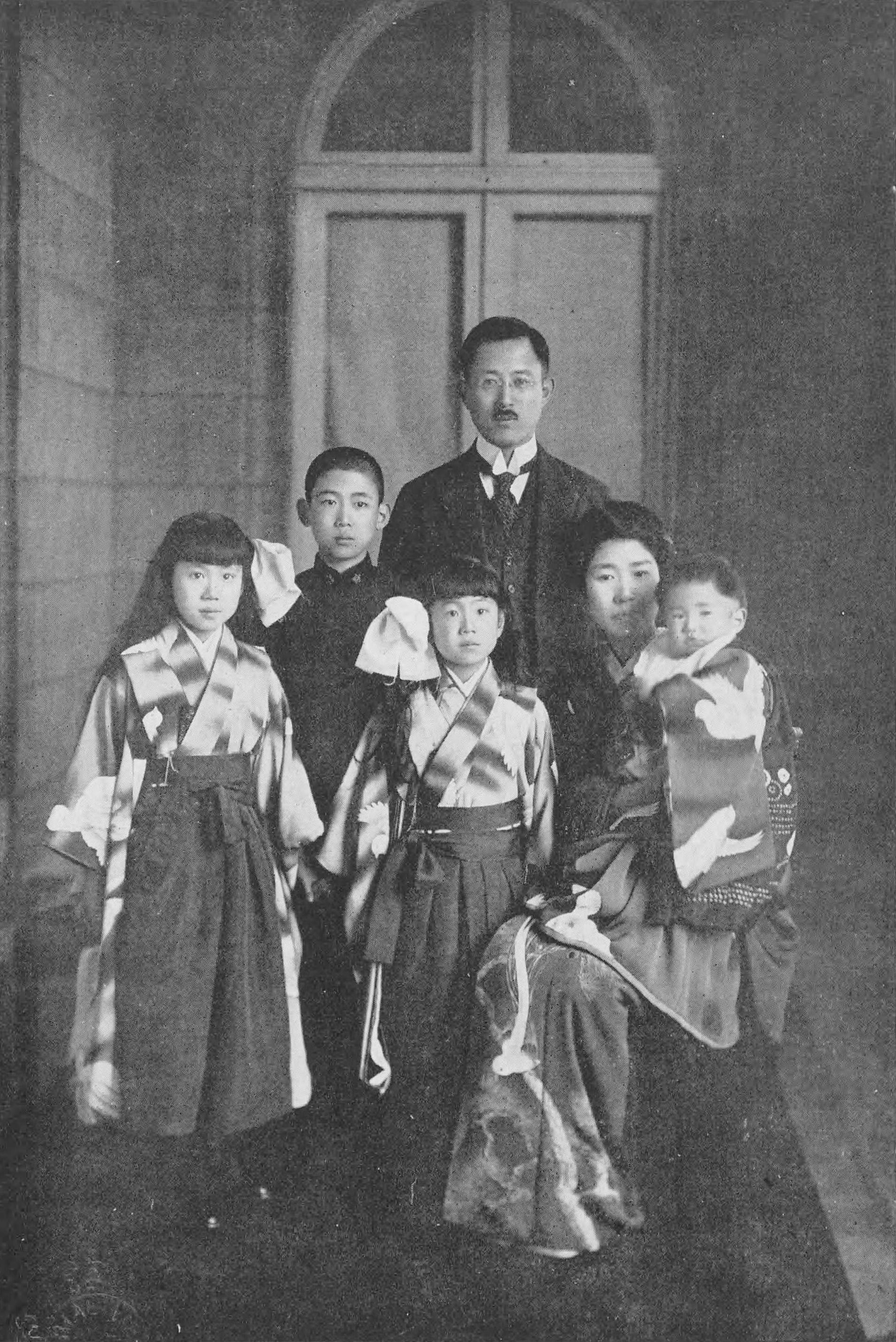

Kubota was born in 1917. He was the son of an antique dealer that resided in the traditional part of his neighbourhood. This would have been during the Taisho era (1912-1926) when a burgeoning domestic and foreign set of markets had opened up to the Japanese industries and on the tail-end of adopting Western customs, manners and attires. which destroyed much of traditional Japanese Arts and Crafts.[1] It may not have escaped his inquisitive eyes that much of this was particularly disappearing around him as he grew into his teenage years into a family of artisanally inclined people. Many of his neighbours were dye workshops, and we can presumably assume that this was were he first began to mix his family social capital inheritance of old artforms with his neighbourhood ties.[1]

In 1931 Kubota began an apprenticeship to Kobayashi Kiyoshi, whose workshop was known for its handmade Yuzen dye work. There Kubota began learning how to paint, dye and the traditional and perhaps contemporary Japanese design aesthetics such as landscape painting, portraiture and other traditional Kimono painting techniques. By 1936 he was considered good enough to establish and build his own dye studio.[1]

Presumably by this time as an established Kimono Komin and Designer, and with his family background in antiques began to search out inspiration and influences from centuries gone by. This took him to the Tokyo National Musuem where he first witnessed the then considered lost technique of design, Tsujigahana which was extant from the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568-1600).[1] At that time of 1937, Kubota was 20. This moment of witnessing such a beautiful moment frozen in time and interaction with the world external to the Museum inspired him to relaim the design into the modern day and age to be enjoyed once again, rather than to be locked away in a case as a lost relic of another time.

The design element of Tsujigahana was created in the time of the Muromachi period (1336-1573). The design of that time were heavily dependent on a kind of conservative tendency towards an almost Iki reading of Ashida-E, Onna-E types of artistic lineages of Art which were heavily image and symbol heavy. These resist dyes thus were able to evoke a heavy sense of narrative and storyworlds in their decoration and in a time which was heavily restrictive in literacy towards women and the lower classes, these textiles were lavishly and painstakingly created most likely by the affiliated workshops and Machi-Eshi Komin capable of working on these unique Tanmono wealthy families could afford, this being the wealthiest Sengoku Daimyo and the urban Chonin. By 1690 with the almost complete decline of Za guilds and the rise of Miyazaki Yuzen's moyo Tsujigahana fell into decline.

This is to my knowledge the most likely explanation as to why Tsujigahana fell out of favour by the later part of the Edo period and completely 'forgotten' by the Meiji (1868-1912). That being that the production of such a textile would have been a trade or workshop secret and therefore died out with its lineage creators, as otherwise a legacy form would still exist in the realm somewhere, in one form or another. This is pretty guaranteed due to the amount of decorative elements, a time-consuming and expensive dyes, metals and embroidery used in the creation of these garments which makes it unlikely that farmers would have been making and wearing these textiles to go rice farming in.[1] Almost as likely as wearing ballgowns to pick maize.

Returning to our protaganist, Kubota was fascinated the mystery of where and how this original technique had been lost. He was under its spell from that point on, making it his life's work to figure out the mystery of that lost technique.[1] Another layer to the fun, was that the silk to create the work was Nerinuki, an archaic textile no longer woven at the time. It would be this step to technique revival which would take decades of work for Kubota, presumably somewhat interrupted by the second world war. Evil Japanese officials ruined the progression of his work by drafting him, where he spent 3 years as POW from 1945-1948. Given the dates, it is most likely he was rather weak and unfit for military service, but at the time Japanese army officials were not particularly picky, sending children and the elderly to fight what was for them another rich mans war. Indeed, it was during this time that Japan's new Constitution declared Japan to be unable to go to war unless in self-defence resulting in the modern article 9 which 'renounced war forever'.

However not one to let a stupid war stop him, he returned to Tokyo and set up shop once more, mostly in Yuzen kimono. By 1955 aged 38, he had decided to fully devote his down (presumably, the early 1950s was a difficult time in Japan, especially Tokyo) time to Tsujigahana revival. In a bid to get it done within his lifetime, Nerinuki was released back to the misty, shrouded hills of Folklore Studies once more and modern silk was deemed good enough. Instead, the technique was the focus, a mix of resist-dyeing and hand painted ink painting.[1] Using chirimen as a base, Kubota dyed each bolt independently and stitched. This formed the basis of Kubota's technique. Whilst this may seem revolutionary for some and a copout for others, this work is symbolic of what an appreciation for the worlds before our own is. An understanding that what we see is but a fleeting (in this case) material remnant, which we build upon in transforming the work to modern needs. This is a more honest understanding of KTC and whilst not a literal remaking, it is indeed a revival of the vision of what a Daimyo or Chonin may have felt upon recieving the same material. A reboot if you will that saw in 1977, Kubota first exhibit his take on Tsujigahana.[1]

This is evident in the series Kubota created for 1979, which presented panoramic views of sunsets and landscapes for example. This was displayed that year, and included 80 painstakingly handmade Kimono. True to his artisanal and nitpicky roots, this series was developed and continued until Kubotas passing onto the next life. It is this spell however which is almost a translation of the glamour of times gone by, a fae tale which has been spun into the gold leaf covered T-shaped works of Art which wealthy patrons swanned around in, a world which archivists, librarians, curators, re-constructionists and art historians have in their everyday. It is the job of the modern designer to translate this to bring these facets of history to a wider audience and it is this message and elements which make us consider Kubota as an archival liberator, that is one who works with firsthand artefacts in the archives left to us to create magic.

Bibliography

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itchiku_Kubota

Socials:

One stop Link shop: https://linktr.ee/Kaguyaschest

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav

https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_for_a_Boy_MET_DP320319.jpg)

_-_illustration_-_page_132.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(BM_1907%2C0531%2C0.66_1).jpg)

_(BM_1942%2C0124%2C0.15_1).jpg)

.jpg)

_with_Carp%2C_Water_Lilies%2C_and_Morning_Glories.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)