In this essay I explore the concept of the arrival of the Business Girl, and the Shufu ( Censored | Housewife ) of the 1930-1970's period of the 20th century.[1] This intersects with how we see Wafuku represented, in a shifting dynamic that had not shifted so many barriers since the 1870s, and even until the 1990s with the intrusion of Euro/Americentric beauty standards being foisted upon the world during these centuries, in the wardrobes of the upwardly mobile single business women of from 1955-1965. These groups came into being in the 1950s with the advent of the eclipse of settler colonialism and patriarchal standards over women's lives internationally. KTC thus developed in response to these changing, testing and trying times (between 1930-1970).

Woman in Kimono with men in uniform (c1940, PD) SSJF01

Interwar period 1919-1940

The interwar years for the West saw the construction in Japan of new GEACPS beauty standards of homoegnous raven haired 'Wamono' beauties stood around, being a good wife, wise mother. Like Shanghai, places like Tokyo and Yokohama were very Western influenced, and highly cosmpolitan, diverse places to be in the 1920's. With their high numbers of foreign born population, cities like these enabled faster adoption of foreign trends, styles and fashions. In a bid to acclimatize to being a great power amongst the 'Civilized circle' of white powers as one of Commodore Perry's 19th century biographers related Japan, Japan heavily lent in to white proximity identity politicking during the early 20th century. Albeit with the aftermath of the rejection of the racial equality clause at the 1919 Versailles Treaty, and as the only POC signatory with a seat at the table, this increasingly isolated Japan from its White 'Counterparts' in the next 2 decades in the throes of Statesian Wilsonian foreign policy decisions.

Albeit GEACPS wanted MORE resources. So Asian countries were also not entirely co-prospering under this system either, even having the double intersectionality identity politics of being non-white and yet being GEACPSed by a nonwhite power. Mmhmm. Following this aftermath, these beauty standards grew heavily more jingoistic by the 1940s, with fashion being not an individual or societal lead activity, but rather a patriotic endeavour where Shufu would patch up old Hakama and use unconventional materials for the good of the Mother Country. These eventually lead to some rather strange propaganda styles on posters and various other wartime rationing fashions which lead more women into the workforce against the chagrin of some people, allowing more women to enter not just the labour force, but the middle classes and business arena than was seen as appropriate before during GEACPS time.

Kimono 1940-1945

I will let the images speak for themselves here, as it deserves at least 2 essays on its own to draw a conclusion about these images.

Jingo Dogwhistle Kimono (c.1940, PD) Japan

Burns correspond to Kimono worn on day of blast (1945, PD) Gonichi Kimura

SCAP rant 1945-1952

The postwar Business-woman was astutely aware of the realities that the 'Pacific' war had been waged between 1941 until 1945, and that they had come out on a losing side. This resulted in a stunted growth in all fields and sectors, with goods and services being heavily diminished until the 1950s in the Japanese domestic economy under the guiding hand of MacArthur Douglas the great shogun of American Enlightenment and White Supremacy SCAP. By the 1950s though, many of the local branches of capitalistic services and goods had returned in some fashion through the black markets which had sprung up in opposition of American/SCAP's shite 1945-46 rice policy decisions* bizarre censorship and market decisions with regard to wartime planning continuation plans.

The 1950s saw the return of brighter, cheerful topics like fashion, and to get around a lot of ongoing rationing, legal kerfuffles and to remain on trend, a large number of previously conservative publishers and industries began incorporating prominently Americentric policies of adopting Western fashions, designers, models, styles and thus transfixed the way fashion was done, not just worn in a bid to meet the rather imposing SCAP demands of the free press as well as keep up with the demands of readers.[1] For more, ask your nearest American industry for more about Ansei protests, r**ing 'the natives', hafu abandonment, the lost War (Korea), MacArthur getting fired in 1951 for his 12 year old comments or the Reddo Pajji. Side effects may include, headache, anxiety, racism and death.

Whilst SCAP was lining up Japan to be another American Neo-colonial possession as with the Phillipines a Communist bulwark domino in the Coldwar Buildup against Russia (as it later tried with Afghanistan in the 1960's-1990s, see Operation Cyclone for more 'freedom' or Wilsonian foreign policy), Japanese economic majors in cities like Tokyo, Osaka and Kobe began to dream up what became the Japanese postwar economic miracle, again the in face of American occupation fever dream policy, which lead to the * and eventually caused the 'Reverse Course' as SCAP realized that 'these Japs know a thing or two about x'.[3]

Kimono (1956, PD) Meomeo15

Business Gyaru

Young, single, urban and working women were targeted at by the glossies and fashion magazines of their times. By 1957, a new golden age for weekly magazines and papers aimed at these demographics began.[1] Most of the fashions at the time were still handmade, and included methods of sewing for Shufu to achieve the desired look.[1] This was the double-edged sword of being a woman in the 1950s, patriarchy was rife, and women were expected to still fit into the good wife, wise mother role of the 1880s, staying at home, cooking, cleaning and being baby factories whilst their breadwinner husbands came home to them for a bath, dinner or me?

During the early 1950s, these spreads often included mostly Kimono fashions, but by the 1960s shifted towards western styles of long skirts, dresses and blouses.[1] 1950's fashions emphasised however the Iki chic diminutive styles of grey, gris and grey for the Business Gyaru.[1] Unfortunately, this timer period still saw women as expendable labour pools only, and upon successfully becoming a man's labour slave, women were expected to quit their jobs, careers and livelihoods to lick the floor clean 168 hours a week for their new husbands.[1] Women in this capacity under patriarchal value systems were still seen to be only suitable to don Kimono, as befitting of the good wife, wise mother.

Office Lady

In the 1960s with the beginning of Womens Liberation movements and the Sexual Revolution, the term Office Lady was adopted to reflect the more appropriate name for fully grown adults going to work, even if they were 'just secretaries'.[1] International popularity for Japan through soft power also grew with the 1964 Olympics bringing increased press coverage, more broadly bringing attention to existing Japanese disapora models like Akiko Kojima (1936-present), Hiroko Matsumoto (1936-2003) and Michiku Shono (dates unknown) who all modelled for high fashion magazines in the West like Vogue and Harpers Bazaar.

Hiroko Matsumoto (1966, CC4.0) National Library of Israel

With this liberated, cosmopolitan and more racially diverse outlook Japanese beauty standards once again shifted. This time, magazines promoted western silhouettes and Yofuku as a 'modern' form of dress, much as using English, smoking and showing ankle was fashionable 'modaan gyaru' behaviour in the 1920s. Fashion of the time promoted the civil rights contention mostly centred in the US, seen after the passing of the 1965 Civil Rights Act and focused on by the Civil Rights Movement. This saw the international response, particularly in London with the promotion of racial diversity to prompt an idea of 'modernity', seeing as they already spoke English, smoked and showed their ankles, with the first POC model to be put on the cover of British Vogue in 1966. With this, the move to fashion magazines saw a move away from Kimono towards western clothes, with Wafuku being considered fashion for older women, a misconception promoted by Western clothing companies from 1960 on to sell more units in Japan.

For those models who did wear Kimono in more conservative roles, tall, slim and western faces with Japanese features became the new beauty standards, following the trends of POC Western models and those set by high fashion models like Twiggy (1949-present), Donyale Luna (1945-1979), Hiroko Matsumoto, and Jean Shrimpton (1942-present) in the 1960s, becoming completely 'hafu' oriented by 1973.[1] Each of these models also interacted with Kimono in their careers and I will probably cover their escapades in upcoming essays to give a more rounded image of the British response to Kimono after 1953 when it was readopted by British dancer Lindsay Kemp back into the popular fold as part of his performances. Unfortunately though, the Kimono received less coverage for Office Ladies than her counterpart the Business Gyaru, and so saw Wafuku fade to memory as 'heritage' pieces for Japanese women born after 1970 and as 'Oriental table runners' for white middle class women after 1952.

Kimono were still worn and were considered highly desirable items in the early 1960s, representing a slew of traditional, moral, cultural and ethical values for some, and a nuanced mix for others in light of recent GEACPS events. Kimono were still worn for their beauty, for their price and for their craftmanship albeit in lesser numbers. Office Ladies would have been part of the drive for 'modernity' and may have shied away from repressive connotations Wafuku would have held for them as 'traditional', 'restrictive' garments, seeing their being replaced in many posh workplaces with the 'modern' western business suit, even, gasp, 'pantsuits'.

Twiggy in Japan (1967, IPI) Anonymous

Conclusion

In context we see how KTC standards were created by the geo-social politics of their times. The 1920s being the product of WWI and colonial settlements and white supremacy resulted in a more cosmopolitan KTC culture for women in KTC, following the liberal openness of Wafuku in vogue since the 1870s, but begun in the 8th century albeit under a colonial gaze. The 1930s brought more jingoistic rationing, and the 1940s saw this turn to a zealous nature with green, brown, navy and rationing card being the name of the game. The 1950s regurgitated these conservative values into the Iki kimono of the Shufu, with women expected to leave their roles as Business girls, even though it was vital work to keep the economy afloat. By 1957 this had laxed, with the development of women's role in society from the 1960s, when Business minded females began to find pockets of prosperity, becoming the respectable Office Lady who lead a cosmopolitan, urban lifestyle, yet the Housewife ideal however was still a pervasive stereotype of the expected womanly role. During the 1970s women's liberation movements began in Japan, seeing a decline in the idea of Wafuku as modern, until the remergence of Wafuku in the 1990s with new internet subcultures repopularizing Wafuku.

Bibliography

[1] Decent Housewives and Sensual White Women - Representations of Women in Postwar Japanese Magazines, Emiko Ochiai, 1997, pp.155-165, Issue Number 9, Japan Review | https://www.jstor.org/stable/25791006?seq=5

*Around 2 million people died between 1945-1946 in Tokyo alone due to a rice famine caused by American supply line bombing of foods, railways and civilian areas during and after wartime, under SCAP's own management, which was dominated by American management. And oh how lovely, they brought in food aid to prevent 11 million more dying 0.0[2]

[2] https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/american-strategic-options-against-japan-1945#:~:text=Famine%20in%201946%20was%20only,saved%2011%20million%20Japanese%20lives.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverse_Course

Essay Abstracts

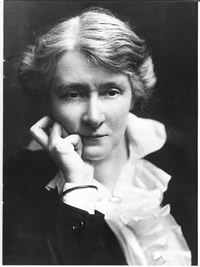

#1 Renee Vivien (1877 - 1909) --- Born Pauline Tarn, was an English lesbian poet. She wrote in French and perhaps English. She took up the style of the Symbolists and Parnassinism and was well known during the era of the Belle Epoque (the Beautiful Age) for producing Sapphic verse and living as an open quasi butch lesbian poet; her verse derived from the ancient poet Sapphos, also famed for her love of women.

# 2 Birth of the Kimonope --- Here I shall introduce the notion of the Kimonope, that is as a garment attached to the social construct of the 'Geisha' in North America. Kimonopes being Orientalized clothing, or 'negatively affiliated or exoticized ethnic dress' which lead to the perceived notion of the Kimono and Geiko as simultaneously both high and low culture to American culture makers, such as film, television, media, writers and some academics. An example of Kimonope are the tacky Halloween costumes you may find at the Dollar store.

#3 The Legacy of the MacArthur Dynasty on KTC & The Problem with the 'Traditional Garment' Argument --- The problem with arguing that the Kimono is a 'Traditional ethnic Garment' is that that assertion is in itself, arguably Ethnocentrism, which to clarify is the imposition of, in this case, American values onto Japanese cultural values, belaying the 3 pronged pitchfork of idiocy.

#4 Divine --- Government name Harris Glenn Milstead (1945-1988) was the infamous North American Queen & Drag artist. Specifically, Divine was known for being a character actor, part of her act is well-known for its eccentricity. My personal exposure to Drag lite was Pantomine Grand Dames as a kid, and later when my friends made me watch RuPaul in art classes, so to me this is nothing new, the over the top, the glitter, the upstaging is all part and parcel.

#5 Dori-Style or 21st century Kimono Fashion --- The Dori-Kimono style. Something which I just made up because in going over notes for the first 20 years of 21st century section of Kimono history, I noticed a lack of a clear catchall term for what was happening in Japan at the time, at least in English descriptions of the time. I use the term Dori as I do not want to coin an unrelated term to the topic, but I also am reticent to claim all of Street style as 'Tori' either, whilst a large number of streets upon which the subculture originates in all use the suffix 'dori' (the bottom of Takeshita-dori for example), thence Dori-style.

#6 The Tea Gown --- This essay will cover the aspects of how 19th century Japanese import textiles to Western countries were used and repurposed, as well what their desirability tells us about how Japanese design was regarded and the image which these people held of Japan through the Western lense and consciousness. This follows the progression of how Kimono can be used in the West from the undress of the 1860s, adapting silk bolts in the 1870s to high fashion western daywear, to the 1880s aesthetic movement and 1890 wholesale adoption in the Victorian age to being used prominently by society hostesses as tea gowns by the Edwardian period, and the subsequent change in Japanese export culture which we see in extant textile collections of Japanese textile in Western dresses of the periods.

#7 Kimono and the Pre-Raphaelite Painters --- This essay will cover the aspects of Kimono in the Portraiture of the Pre-Raphaelites. The Pre-Raphaelites were a group of British artists and writers active during the late Victorian period. Unlike the Royal Academy artists, this circle of painters operated outside of the established comfortable boundaries of the expected white, cisgender middle class audience of the Victorian age. The movement is notable for its inclusion and encouragement of women, and in portraying and engaging non-conventional beauty and beauties as figures from the Classical World alongside Religious, Mythological and Folklore Heroines into Victorian 'Femme Fatales'.

#8 Jokyo/Genroku Kimono Textile Culture and the new role of the Komin --- This essay will return back to GKTC (Genroku Kimono Textile Culture ; 1688-1704) and JoKTC (Jokyo K.T.C. 1684-1688) and the new role of the Komin (Artist caste) in GKTC. JoKTC is notable for being the lead up to GKTC, JoKTC being characterised by its transitory nature in comparison to GKTC, which was far more bold in its relations to what Kosode could and should be. Komin entered the picture at this juncture, and I shall elaborate a little more here than in other posts about why that was. GKTC is notable for its elaborate, perhaps gaudy and innovative Kosode design features, whilst JoKTC more so for the enabling factors of the time, as a sort of incubatory GKTC.

#9 Tagasode Byobu - This essay will explore the art motif known in Japanese art as Tagasode Byobu ( Whose sleeves Screen) This motif is a recurring art form which was particularly popular during the Azuchi-Momoyama era ( 1568-1600 ) as a representation of the ways in which Buddhist sensibilities met with the fast changing events of the end of the Sengoku Jidai (1467-1615) and as an extension of the habit of wealthy women from military families came to own and store a large number of Kimono. Prior to this, Kin Byobu ( Golden Screens) for the most part depicted nature like Sesshuu Touyou (1420-1506) after Chinese Cha'an painter Muxi ( c.1210-1269 ) or 'flower-and-bird' scenes like those of Kano Eitoku (1543-1590), rather than humans or human paraphernalia as an extension of the Zen painting school of thought about materialism.

#10 Cultural Acculturation --- The topic of our essay is on the nature of Cultural Exchange in KTC which will be an ongoing mini-series throughout 2022. This covers the 1000CE - 1500 period in Japanese History.

#11 Cultural Appropriation --- The topic of our essay is on the nature of Cultural Appropriation which will be an ongoing mini-series throughout 2022.

#12 Cultural Acculturation --- The topic of our essay is on the nature of Cultural Acculturation which will be an ongoing mini-series throughout 2022. This covers the Asuka (Hakuho), Nara (Tempyo), and Heian periods (500CE-1000CE) in Japanese History.

#13 Asai Ryoi --- This essay will explore the legacy of Asai Ryoi on KTC. Who was Asai Ryoi you may ask? Only one of the most important writers for the Ukiyo genre. Asai Ryoi ( act. 1661-1691 ) was a prolific Ukiyo-zoshi ( Books of the floating world ) or Kana-zoshi ( Heimin Japanese Books ) writer. His leading 1661 publication, lambasted and satirized Buddhism and Samurai culture of restraint in favour of the Chonin lifestyle of worldy excess.

#14 Edith Craig --- This is a post regarding the early adoption and promulgation of the Kimono and Japanese aesthetics in the life of the wonderful Edith Craig (1869-1947), daughter of the famous actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928) and Edward William Godwin (1833-1886). Edith was also known as 'Edy'.

#15 European Banyans --- This essay will explore the European garment known as a Banyan, which originated as a European reaction to Kimono in the 17th century, popular until the end of the 18th century. The word Banyan originates from Arabic ( Banyaan), Portuguese (Banian), Tamil ( Vaaniyan ) and Gujarati ( Vaaniyo ) loanwords meaning 'Merchant'. Alternative versions saw the item fitted with buttons and ribbons to attach the two front sides together. The Banyan was worn by all genders and was particularly regarded in its first iterations as a gentlemanly or intellectual garment worn with a cap to cover the lack of a periwig, and later adopted by women and greatly influenced how British womens garments were designed with preference for comfort in removal of panniers whilst maintaining luxurious, modest 18th century fashions (see Robe a la Anglaise).

#16 Miss Universe and Kimonope --- This essay will explore how Beauty Pageants, principally Miss Universe, has engaged with KTC. While there may be real Kimono worn by Japanese and Japanese adjacent contestants in the 'National Costume' category, I will be focusing on the Kimonope worn by contestants. The idea of Kimono as a 'national costume' sparks interesting conversations on what 'national costumes' are, their target audiences, and how we form ideas about these things to begin with.

#17 Onna-E --- Womens pictures refers to the Nara, Heian and early Kamakura ( 710-1333CE ) practice of drawing women in elongated Hand scrolls, which today are regarded as feminine gender coded Art. Some of these narratives depict the lives of women, their extra diaries, or the literature they wrote. The Onna-E style derives from how mostly Heian women represented themselves and others as a performed self in these scrolls, drawing from their lives indoors at their and the imperial abodes. Whilst a limited number of women could read Kanji, they also used their knowledge of Chinese culture to create and inspire their own culture; the first truly Wamono aesthetics; and it was with these preconditions that Onna-E became established in the Japanese art scene alongside Yamato-E and Oshi-E.

#18 A Jamaican, a Monster and Portuguese bar in the Orient --- This essay looks at the Kimonope attire adopted by North American Dancehall artists Shenseea (Chinsea Linda Lee | 1996 - present ) for the video to 'ShenYeng Anthem'. Whilst the aesthetic derives mostly from East Asian, principally Chinese aesthetics, the language used is specifically Japanese, referring to Chinsea Linda Lee as 'ShenYeng Boss', a perpetuation of the Dragon Lady stereotype. The essay mostly charts how this ridiculous Kimonope derides from the North American Anti-Chinese movement and how this intersects with contemporary Orientalism.

#19 The Red Kimonope --- The Red Kimono is a terribly named racist US silent film from 1925. The Longingist film includes a key scene which the production gets its name from where the protagonist drops her Kimonope, meant to symbolize that she had turned away from sin and prostitution, or in other words equating a wearer of the Kimono as a sex worker which stemmed from another American 'tradition'. This dreadful melodrama features the previously yellowface-accepter Priscilla Bonner as the lead protagonist. Throughout her trials and tribulations, she faces many ups and downs, like becoming a white version of the Lotus Blossom stereotype, because WASPs. I will explore the origins of the Lotus concept and the 'Jade' in more detail here as to provide the contextual background of the productions symbolism.

#20 Housewife, Business Girl, Office Lady --- I explore the concept of the arrival of the Business Girl, and the Shufu ( Censored | Housewife ) of the 1930-1970's period of the 20th century.[1] This intersects with how we see Wafuku represented, in a shifting dynamic that had not shifted so many barriers since the 1870s, and even until the 1990s with the intrusion of Euro/Americentric beauty standards being foisted upon the world during these centuries, in the wardrobes of the upwardly mobile single business women of from 1955-1965. These groups came into being in the 1950s with the advent of the eclipse of settler colonialism and patriarchal standards over women's lives internationally. KTC thus developed in response to these changing, testing and trying times (between 1930-1970).

Social Links

One stop Link shop: https://linktr.ee/Kaguyaschest

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav

https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/

.jpg)

.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_por_Ku_K'ai-Chih._Copia_de_la_dinast%C3%ADa_Sung_(960-1279)_seg%C3%BAn_la_obra_original_del_siglo_%E2%85%A3.jpg)