This essay will return back to GKTC (Genroku Kimono Textile Culture ; 1688-1704) and JoKTC (Jokyo K.T.C. 1684-1688) and the new role of the Komin (Artist caste) in GKTC. JoKTC is notable for being the lead up to GKTC, JoKTC being characterised by its transitory nature in comparison to GKTC, which was far more bold in its relations to what Kosode could and should be. Komin entered the picture at this juncture, and I shall elaborate a little more here than in other posts about why that was. GKTC is notable for its elaborate, perhaps gaudy and innovative Kosode design features, whilst JoKTC more so for the enabling factors of the time, as a sort of incubatory GKTC.

Shibori Chrysanthemum Kosode design ground on Indigo Satin (17th century) Tokyo National Museum

Land to Money Economy

During the Muromachi period (1336-1573), local coinage supply was insufficient and too sporadic to totally meet Japanese demand, and was supplemented by Ming Chinese coins. Instead, the economy was regulated in Rice stipends by the Kokudaka (rice system?) as a land economy, overseen by rice brokers, who made their money by storing Daimyou rice crops in their storehouses. However with the end of the Sengoku Jidai and stabilisation policies promoted by the Tokugawa, coins began to become a rival form of currency by the Tenna period.[3] By this time, the Kyoto and more so Osaka ricebrokers had developed comprehensive networks of storehouses, which they exchanged for tickets, an early form of paper currency. As the economy stabilised and the need for war evaporated, and domestic market demand increased[14] A system which dirty dirty Chonin (in the mind of the Kuge) came to use as they were unable to make ends meet by hoping Kuge senpai might notice them. By 1601, coinage became standardised. Local trade networks for things such as imported goods and 'dirty' trades developed, and on the back of this Chonin began their own business between 1610-1630, bolstering work for tradesmen (cart-sellers and day labourers).[1][2] From 1635 the abolishment or decline of trade monopolies in the Bunkoku 分(国 ; trading zone) by the upper class merchants (the likes of Murayama Tōan) from schemes like the Itowappu Nakama (Silk Guild), broke up even more industries into wider unregulated trading goods. Urbanisation from 1635-1665 then saw to the rise of cottage industries to supplment the replacement of rice to coin.

1666-1681

With the lasting effects of population upheaval, the rise of the merchant class and transfer of wealth distribution from samurai to Chonin castes, the landscape of Japanese demographics changed heavily from 1635-1660. The Kambun (1661-1673) and Enpo (1673-1681) eras saw mild shifts in the acceptability of beauty standards, a shift in power dynamics between geo-political centers of soft power figureheads, and the rise of the printing industry.[1] This led to the Yakusha-e, Hinagata Bon and many other images and rules surrounding the acceptability of fabrics, conduct, expense, design and persons surrounding the design of Kosode.

Kosode Designs (1677) Hishikawa Moronobu

Kosode at the time conformed to both regulations and certain beauty standards. Regulations depending on the era (becoming more stringent after 1670) often forbade Chonin from taking on particularly luxury fabrics and dyes like gold, red, or some silks and wearing them in public. Beauty standards forbade this as well, so simple was the call of the day for Kosode designs in Hinagata Bon of the day. Kosode in this time often had colour schemes strictly of no more than 2-3 colours for wealthier Chonin, and the Heimin (farmers, leather workers, tanners) often made do by having a single base colour which contrasted against another relief design feature such as Shibori. Beauty standards often encouraged the design to incorporate Japanese motif instead by referring to allegory, scripture or popular culture instead of splashing the cash.

Therefore from 1608-1665:

- Rise of the publishing industry (1608-1670)

- Land to Money Economy (1615-1660)

- Urbanisation (1635-1665)

1681-1684

In the Tenna period the delicate balance of societal wealth distribution fell in favour of the Chonin, who by now had amassed a wealth greater than the stipends of their samurai counterpart's Koku stipends. The Tenna period saw the rise of local industries particularly around the production of Japanese made silks, as part of the governments fights with Chinese and Japanese piracy and tariffs on incoming Chinese silks which were being sold on the cheap. With this came the decline of the trade guilds in the Bunkoku and the rise of the thrifty Chonin wholesale merchant.

Osaka

Osaka in particular was known for its nifty and thrifty Chonin who had a large market share of rice brokerage.[14] With the ebb and flow of the Itowappu system, this gave rise to the financial power of the Chonin (almost black) market by 1685. Osaka merchants lived nearby to import markets and also to Kyoto, where most silk was produced at the time, making it an ideal location giving its already built up infrastructure, and cheaper prices than Kyoto levels. Osaka merchants prominently were known for their wealth, and were reknowned for their nouveau riche lifestyles as such due to their newfound wealth, a regional Japanese stereotype which has stuck ever since.

However whilst particularly prominent in Osaka, all Chonin during Tenna more so appreciated the finer; material, things in life. Samurai were more so at the time buying other goods such as roof tiles for their leaky palaces and creaky moats. Chonin tastes had with their abundant mastery over their own little corporations, come to enjoy greater say in the wider society they lived in as wealth distribution shifted in their favour. In this way, Chonin became the arbiters of taste during the Tenna period when regulations were somewhat lax and spending habits high.[6]

With increased expenditure however, came more problems for the Chonin. Problems such as their refinement, karmic influence and worldly standing. It was a world of hedonism certainly by Medieval European standards, and this saw the launch of popular trends amongst Chonin. Chonin would often compete to outdo the other, certainly in the bigger cities of Osaka, Edo and Kyoto. Kosode design became more elaborate and distinct, allowing the Heimin a complicit understanding that the wearer of finer Kosode were well-to-do, well off and were learned individuals, literate in the Buddhist texts, popular tales of the day, the classics, up-to-date on the latest art trends and who had access to the latest and greatest Kabuki and cash-spalshing textiles such as fine silks, gold embroidery and the ever coveted Beni. As such, artist became ever more involved in the creation of these elaborate Kosode, as they became evermore bespoke and tailored to their first wearers.

The Four occupations (1883) Ozawa Nankoku

The Artisans

Komin, otherwise known as the artist group under Confucian teachings, forming the theoretical Ko caste of the Shi-no-ko-sho ( Four Occupation Groups; Scholars/Warriors: 士 Farmers/Heimin: 農 Artisans: 工 Merchants: 商 ) which had been in use in China since their Warring States Period (403-221BCE) and introduced by the Tokugawa in their bid to bring about stability.[4][5] Often in Tokugawa Japan however, the Ko and Sho castes overlapped frequently, and as such, are an unreliable category set but are useful as a framework understood at the time by Japanese writers. A Komin as such, is a person who makes art, or works in a craft. For Japanese creatives, this is a blurry distinction as art and crafts are one in the same process, unlike in the West when during the Renaissance they split under secularisation during the Enlightenment period through the rationalism (in the art world, nature) vs empiricism (mechanised) debates into Art (divine works of nature) and the lesser crafts (mechanial and hand labour work) in the Occident. Komin often were poor creators, and relied heavily on the patronage of wealthier clients and patrons, particular in the 17th century.

Komin as such accepted work for clients. At the beginning of the 17th century, most of their work was more purely religious based iconogrpahy to accompany religious texts or to adorn castles, later alongside Buddhist catechisms. This changed though, with the inclusion of increasing numbers of wealthier Chonin merchant clientele in the later half of the century. Komin would principally still at first be asked to create images or scrolls for religious or pious reasons in the 1650s. By the 1660s, the scrolls begin to become a little saucier, a bit of neck, some wrist here and there. By the 1670s the mass print has become available for pennies, and by the 1680s these have become full on Abuna-e, Richards, Lady Gardens and all. These tastes would have been reflected in the homes certainly of a few Chonin, as these were printed and bought by the masses, not just the sleazier Sho.

As such great relationships between the Komin and Chonin had developed by the 1670s. These symbiotic relationships complemented one another when we consider that if a book wasnt selling like hotcakes, the addition of a good painter and some Abuna-e certainly may shift it from the peddlers streetside cart or Gyosho Bako (Merchants box). The earlier and more interesting melding of the Komin and Chonin though however may more likely have come from earlier channels. Evidence exists that as Chonin became ever more regulated under the Sumptuary regulations of the Tokugawa, they sought other avenues to spend their lavish fortunes. This by the 1660s had become Kosode, as evidenced by the Hinagata Bon, the earliest extant examples of which come from 1666.

Kosode as such were being designed by Komin book illustrators, painters, and designers. This was beneficial for the Chonin, as whilst imparting their well placed patronage of the arts and reflection of their knowledge of the Chinese classics in their choice of motifs, it was also a wise investment, as when the Kokudaka collector came collecting, he had no warrant to collect Kosode, which unfortunately for the state, was not rice. Iemitsu really liked rice you see.[5] Instead, by the 1690s certainly, this proponent of Osaka and Edo Kosode design, had become one of the main features of GKTC.

Hishikawa Moronobu

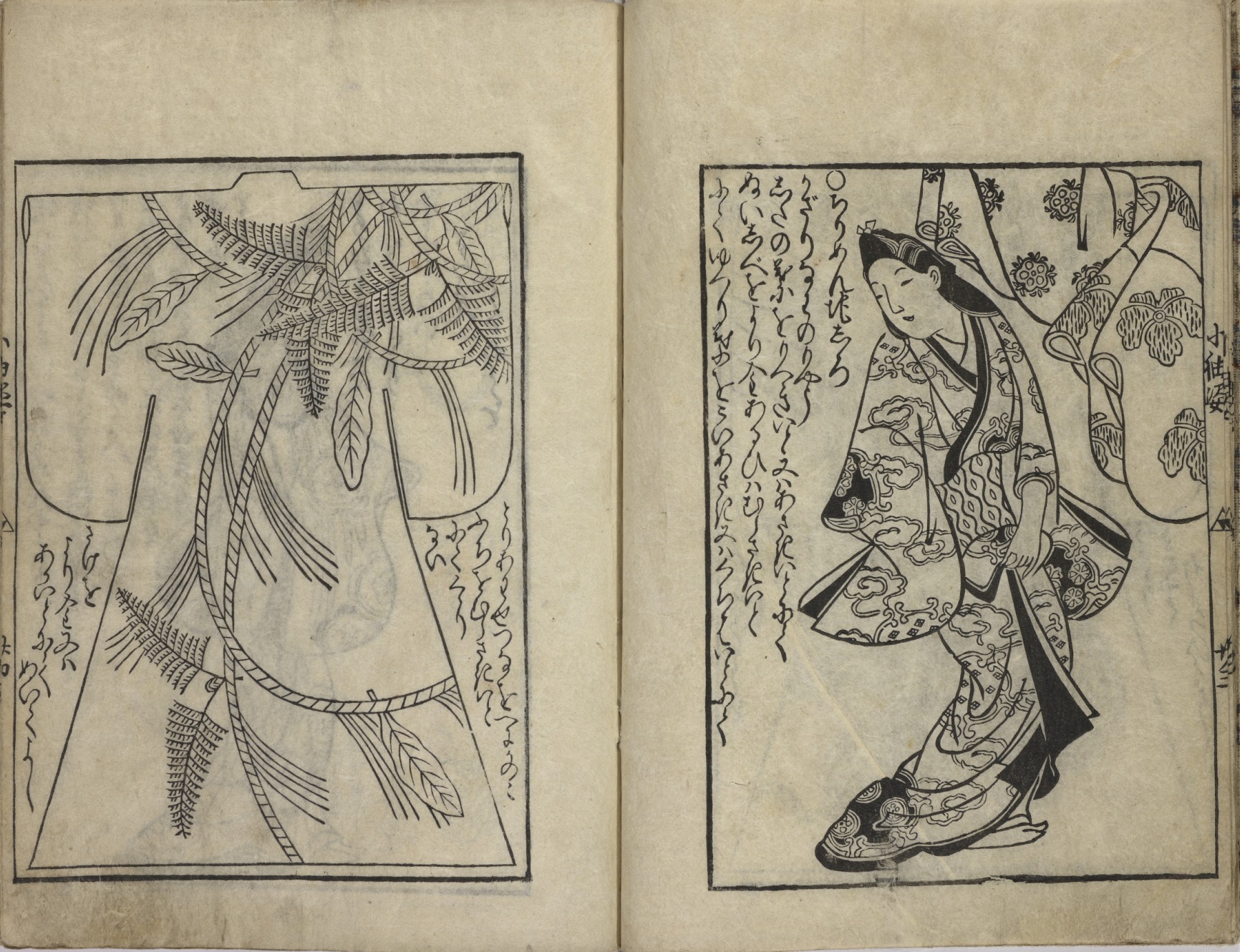

Hinagata Bon and Wakashu (1682) Hishikawa Moronobu

100 Japanese Women (c1685-1694) Hishikawa Moronobu

Hishikawa Moronobu was a defining Komin of the 1670s and 1680s lead in to Genroku period. From 1683, his publisher was Urokogataya Sanzaemon active c1677-1694).[7] Indeed by the Genroku period, Moronobu was considered to be the founder of Ukiyo-e, such was his popularity. As a Komin, Moronobus style was greatly admired, and his personal style became one of the most desired formats at the time.[8] Moronobu, who came from a family of textile designers, contributed to GKTC in his creation of Hinagata Bon to capitalise on his success. His designs were not particularly groundbreaking, often relying on Buddhist iconography in their motif, but were more so popular in the Abuna-e, which most likely caused Moronobus Wakashu styled Kosode to enter vogue.[9]

Yuezen Hiinakata

See the right hand side Kosode for the effect (c1686) Unknown

Yuezen was a significant trendsetting monk Komin who made large text and calligraphy painting styles popular on Kosode. Yuezen developed a vogue in GKTC for large calligraphic text to sprawl across, usually, the right hand side of the upper Kosode sleeves and back, imitating the style found on Kakemono scrolls.[11] This style was popularly designed using Shibori or stencilling techniques at the time.

Yuzen Miyazaki

Yuzen influenced Kosode (c1700,CC1.0) Daderot, Ishikawa Prefectural Musuem of T. Arts & Crafts

Miyazaki (1654-1736)[6] was a fan painter and creator of the Yuzen dying technique. Yuzen contributed to GKTC by creating Yuzen dyeing by applying rice paste to resist-dye cloth, which he called Yuzen-zome ( 友禅染 | resist-paste design ). His painting style was also immensely popular and featured on a number of Kosode from the time by painting his fan designs directly onto the surface of Kosode which became popular by 1688. By 1690, Yuzen had become a widely established tecnhique which was popular certainly with the Kyoto Chonin classes.[10]

Ogata Korin

Karamonoya store, these spread Korins art across Japan (1798) Niwa Tohkei

Ogata Korin's family owned a family goods store in Kyoto in his younger years, which supplied textiles to the Empress Toufukumon-in (1607–1678) at her court, which inspired his own designs reflected by incorporating textiles design techniques such as repetition stencilling into his paintings and screens. It is likely that this will have been how Ogata the painter and Ogata in the textile world were introduced to one another. Korin certainly set the late trends of motifs at the end of the Genroku period. By 1700 these had become Korin monyou (motifs) which were popularly reproduced in varying styles in Hinagata Bon, which were mostly bought by the wealthy or elites of Kyoto who could afford them. These patterns became popular when Kabuki actors wore them onstage, setting the trend for these designs and thus disseminating them amongst the general populace. Examples included Ogata's rounded flowers and distinctive shading. His customers included Nijō Tsunahira (1672–1732), Nakamura Kuranosuke (1668–1730) and Sakai and Tsugaru Daimyo families.[6]

The Komin therefore played a definitive role in the development of the new aesthetical and DIY craft sensibilities brought into vogue in GKTC. When Chonin became their patrons, Komin's work was elevated to new heights in setting trends and defining popular new design aesthetics. Komin frequently were already established as painters or from wealthy families already familiar with textile design, which is how the easy switch of occupation from potter, painter or weaver to designer was allowed, celebrated and circumvented in Japanese society. This was accomplished however, by the elevation by previously unfit peoples, such as the money handling Chonin class, into the Komin class as a way to elevate the station of the Chonin themselves befitting of their new monetary and financial clout without threatening the status quo held in the Shinokosho system in the Genroku period.

In context therefore we can see that the Tokugawa stabilisation policy led to deliberate and direct control of the import/export market through the transformation of the Japanese economy from a land-based to money-based society. These had the effect of increasing urbanisation which led to the growth of local home industries owned by wealthy Chonin, primarily for our interests in the concentration of publishing. This increase in wealth distribution altered the layout of the landscape of art patronage, leading to an increased visibility of Chonin as tastemakers, following the Kabuki actors who were trendsetters.[12] This was primarily by 1688 lead by the Kyoto and Osaka merchants who defined tastes by their patronage of particular Komin.[13] Komin therefore heavily influenced popular GKTC, as they became the innovators of new dye, painting and motif techniques such as the Yuzen dye technique. This lead to the advancement and progression by 1700 of established GKTC, a particularly more 'crass' set of design aesthetics than the leading samurai classes hoped the Heimin to hold. Essay# 9 will cover a little on Tagasode Byobu.

For more see this lecture : https://www.japaneseartsoc.org/2021/04/lecture-the-birth-of-fashion-in-japanese-textile-art/

Bibliography

[1] See Bijin #8

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_currency

[3] From the Tokugawa period to the Meiji Restoration, Eijiro Honjo, 1932, Vol. 7, pp.32-51, Kyoto University Economic Review

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_occupations

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edo_society#Four_Classes

[6] https://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/ars/13441566.0047.006/--sartorial-identity-early-modern-japanese-textile-patterns?rgn=main&view=fulltext#N2

[7] https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG7145

[8] https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG4068

[9] See Bijin #2

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miyazaki_Y%C5%ABzen

[11] https://fashiondocbox.com/Accessories/70488710-Toomey-1-kosode-and-the-class-system-of-edo-period-japan-caroline-toomey-art-history-106-art-in-east-asia.html

[12] See Bijin #3

[13] https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%85%83%E7%A6%84%E6%96%87%E5%8C%96

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rice_broker

Social Links

One stop Link shop: https://linktr.ee/Kaguyaschest

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav or https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/ or https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/

.jpg)