This is a post regarding the early adoption and promulgation of the Kimono and Japanese aesthetics in the life of the wonderful Edith Craig (1869-1947), daughter of the famous actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928). Edith was also known as 'Edy'.[1]

A little background on Edith is that she was from Childhood aware of and involved the adoption and cross cultural embrace of Japanese culture, fashion, and Art with a capital A. Edith grew up as the non-wedlock love-child of Terry and the architect Edward William Godwin, originator of the term 'Anglo-Japanese style'. Both her parents had a great interest in Art and Japapanese culture due to her fathers near maniacal infatuation with Japanese ornament (in the architectural sense), which became a main feature of her parents lives after the man was introduced to Japanese arts in 1862 during the London Exhibition. Edith thus grew up with Kimono and other Japanese stuffs around the family house until her mother seperated from her father, and they eventually went to live in seperate houses.

Growing up in Victorian England, and perhaps even for todays standards, Edith was quite out-of-the-norm. She grew up in this cosmopolitan atmosphere and lifestyle, and was deeply cosmopolitan in outlook and action, recalling much of childhood being 'barefoot' and dressed in 'Japanese clothes'.[3] Her biological brother also carried on this tradition of infusing Japanese Art into his work in theatre spaces by using Noh theatre and aesthetics to underline his own work, with her mother (who outlived her father by decades) also being incredibly receptive to Japanese emigrants such as the actress Kawakami Sadayakko (1871-1946) whom she patronized during her speed run tour of Europe between 1900-1903.

The Adoption Phase

Under this climate of intercultural acceptance or the 'Adoption' of the Lacambre base model, it was that at this time Japanese art began to be adopted with greater frequency into design and high arts in Europe.[4][5] The Turdman himself gave away a Kimono (images also here), most likely bought from Arthur Lasenby Liberty (1843-1917) at the Farmers and Rogers Oriental Warehouse. This is a type of Wafuku used to sleep (a Yogi) in whose construction is slightly different to a Kimono becuase the armhole is completely attached to the body.[9] The item itself is orange and cream in an Asanoha pattern.

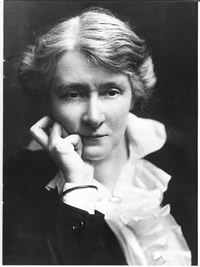

Here is Edith Craig, Ellen Terry’s daughter, wearing a kimono 👘 given to her by the artist James McNeill Whistler. Whistler was close friends with Edith’s father, Aesthetic architect Edward Godwin. #MuseumWeek #MuseumsUnlocked @WhistlerSociety @SmallhytheNT pic.twitter.com/rwjlgwN2Zf

— Nicci Obholzer (@nicciobholzer) May 14, 2020

'if you desire to see a Japanese effect you will not behave like a tourist and go to Tokio. On the contrary, you will stay at home, and steep yourself in the work of certain Japanese artists, and then, when you have absorbed the spirit of their style, and caught their imaginative manner of vision, you will go some afternoon and sit in the Park or stroll down Piccadilly, and if you cannot see an absolutely Japanese effect thereect, you will not see it anywhere.' [7]

Frequently, Wilde and other prominent Queer affiliated British artists of the time active in Aestheticism (1868-1899) looked to first Hellenic, then Japanese culture to derive forms of beauty into their lives. This is most likely to have been due to the fact that both of these cultures were known to have had accepted forms of Queer (particularly gay) presentation in both and thus allowed LGBT peoples to push forwards acceptance and tolerance of Queer content and forms of beauty under the banner of 'Classical Art' appreciation. Physical culture also probably helped.

People like Edith who had been brought up wearing, using and admiring Kimono in this time thus helped to proliferate Kimono in their daily lives as an acceptable household item of Fine Art, loungewear and symbol of luxury. Kimono during the Assimilation period (1890-1915) in British KTC became known not just as a facet of the Mikado (1885) costume designs, but was increasingly commonplace in upper and middle class households. This is particularly poignant when we remember that as a producer of Kori's Yoshitomo (1922), Craig would have been showing and choosing which Kimono the cast would have worn and thus what a 'white' majority audience were being exposed to, and was entrusted to be done by a native Japanese wearer of Kimono.[10]

In this sense of removed appreciation, Kimono became assimilated into the daily garments worn by the Victorians and Edwardians. Figures like Wilde, Renee Vivien[8] and Edith Craig helped make the link to LGBTQIA peoples that Gay and Lesbian history and art existed by making the link to Japanese and Greek motifs of homosexuality and Sapphics in their work and lives meant to be imitated and adopted by the masses.

In context therefore, we can see how Craig is piecemeal of the evolution of the appreciation of Kimono as global KTC and fall under the adoption (1870-1890) and assimilation (1890-1915) phases.[4] Kimono wearing by Edith was initially an attempt by her parents to rear her in a TotalDesign enviroment meant to evoke beauty and purity during the Adoption phase of Aestheticism. Under the Assimilation phase, figures like Edith drawing on their own childhood interactions with Kimono, made the Kimono a mainstream garment for everyday use in their own homes, which spread the popularity and awareness of Kimono in British middle class society. It also tied the Kimono in the historical and popular imagination as no longer and exotic garment, but earmarked it as a Queer garment increasing the popularity and appeal of Kimono as a global garment for use in various stations and peoples in the Theatre and Art worlds primarily in the late 19th century.

Bibliography

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Craig

[2] https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/issues/issue-index/issue-11/little-theatres

[3] Helpers at the Scottish Exhibition, Margaret Kilroy, April 5 1910, p.455, Votes for Women Newspaper, Women's Social and Political Union

[4] Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: T. Dogwhistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan, Ayako Ono, 2001, pp.5-176, Glasgow University

[5] Les milieux japonisants a Paris 1860-1880, Genevieve Lacambre, 1980, p.43, The Society for the Study of Japonisme (Edited), Tokyo

[6] See Essay #6

[7] Intentions: The decay of lying; Pen; pencil; and poison; The critic as artist; The truth of masks, Oscar Wilde, Percival Pollard, 1889[1891,1905], p.47

[8] See Essay #1

[9] https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/4755630/Binder1.pdf

[10] Kori Torahiko and Edith Craig: A Japanese Playwright in London and Toronto, Yoko Chiba, 1996-1997, p.445, Comparative Drama

Social Links

One stop Link shop: https://linktr.ee/Kaguyaschest

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav or https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/ or https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/

No comments:

Post a Comment