Yuefu are a Classical Chinese type of ballad, which falls into the folksong category of our times. Most Yuefu were derived from poetry, a good number by women and then composed into songs. Think sort of like the 1930's poem 'Strange Fruit' which was later sung by Billie Holiday for example. Later dynasties imitated the style of these and these ballads and spoekn poetry styles are now all referred to as 'Yuefu' folksongs, just as Noel Cowards 'Mad About the Boy' has been done with over the past century in English.[1] Yuefu have chronicled the rise of acceptable beauty standards which I put into context and relation for existing within East Asian beauty standards using modern ideas of those times.

Folk Literature

Historically, Yuefu referred to the literal term 'Music Bureau', during the Antiquity or Imperial Chinese historical period, when mainly male scholars would write down the lyrics of contemporary and older ballads for posterity during the Han dynasty when new ideas about how art should be regarded were being debated in elite scholarly circles in China. Historical Yuefu are often unevenly lengthed, fixed-rhythms. Modern versions loosely have five character fixed lengths, and this new standard form came well after 450 CE.[1]

You may be thinking, how does this relate to the development of our study of Bijin in Eastern Asia and its trickle down economy to Japan. Well, a bit of a mystery to me as well becuase there is very little research done on the topic in English and sadly I do not speak nor read particularly well any form of Ancient or Modern Chinese. However, it is known that these ballad songs were often written about archetypes, which included beautiful women, which certainly tells us about the types of beauty from that time and the ideas of what beauty standards even were. And apart from say the Dahuting Tomb Murals which only reflect the acceptable beauty standards of the dead and upper nobility, Yuefu are rather more exciting as they are more of a democratic force for beauty standards.

Meiren in the popular imagination

We can appraoch Yuefu as our current default settings for Beauty standards we can prove existed in Antiquity Eastern Asia. They reflected dominant, upcoming, isolated and universal beauty ideals for women and men perhaps, and formed the pool of evidenced Han Beauty standards by the time the Bureau of Music began recording them. These are the early evidenced examples of course and controversies in their collation, collocation and semantical deviation and focus is of course, like all things Statesian Alex Lomax to be brought into question. However as the archeological and oral record stand, these are our default base settings to dominant East Asian beauty standards.[2]

Many of these folksongs infact begin their lives before the Han Dynasty as tales like those of Xi Shi.[3] Many of these songs are heavily likely to have been not only about, but by women who would have performed these kinds of performances as poetry, dances, recitations and the like to appropriately distinguished scholars and elites as sex-workers, dancers, scholars, poets, attendants and performers. These became a mainstay of performance in elite circles by the late Han Dynasty (c.200 CE) and these performers and poets became celebrated in the popular imagination of their circles, admirers and as muses.[2]

Women had long being holding public office, writing and power since the time of the Duchess of Wey, Ms.Nanzi ( active 534 - 480 BCE ) in lieu of her gay husband, Ban Zhao ( 49-120 CE ) of her writings & Empress Jia Nanfeng ( 257-300 CE ) for her disabled husband.[6]

Most Yuefu were sung from the point of a heroine about the loss of their partner, whilst the lurid in the semantical sense Songs from the Jade Terrace equivalent was their successor the objectifying Gongti of the Tang Dynasty which reimagined Yuefu to a more erotica-fuelled vision.[2] This ideal of Yuefu arose around the time that Yuefu became the democratically and publically performed chaste event they were at the time at the end of the late Han Dynasty (150-200 CE).[2] This was the development of the Damei or Great Beauty, a natural beauty who focused her beauty inwards and towards authenticity, which develped in the Arts as the Lotus Beauty, a reflection of Xi Shi's role as one of the Four Great Beauties of Imperial China.[3][6]

Yuefu were transformed into more erotically charged poetry compilations of women fanning themselves over their wash-basins and rouges, albeit within a patriarchal time which espoused Confucius, Dao and submissive female elites by heteronormative men (c200-500 CE). This atmosphere resulted in the beauty standard of the Nymph Beauty, a sort of ethereal beauty real women could never aspire to, but were judged by. This was the time of Cao Zhi (192-232 CE) and Kaizhi's (345-406CE) Nymph Beauty afterall.[2][4] These metaphorical, ephemeral beauty standards chastised even Empresses, such as Admonitions of the instructress to the court ladies aimed at the Empress Jian Nanfeng (257-300 CE).[5] Jian was respected as a type of beauty, but not as a ruler by her male subjects who patronised her for what they themselves did.

Woman Poetry, Feminine Beauty

New female poets came to power at this time with all of the male drama (wars causing instability) going on around them, asserting new beauty standards which reworked the existing genres. Later Yuefu of the 6th century (500 CE) revived the older traditions of the late Han to form their own rebuke to the 'Abandoned Women' and bitten peaches (Queer love) tropes of Gongti and which formed the basis of new Gongti poetry.[2] This lead to a decline in Gongti by the early Tang period as women came to political power proper, holding influence over the Imperial throne, politics and property.[2] This is reflected in the 14 poets of the Jade Terrace anthology (c.500-589CE) who were female which used Yuefu conventions to do so in 700+ works and which defined female beauty standards of the 5th and 6th centuries.[2][4] Fashionable topics included the Great Meiren, of Inner Beauty, Xi Shi and Outer Beauty Diaochan.[8]

[Beauty standards then were Black] hair with precious stones, slim build and small features. These were what drew court artists to their subjects, with commissioners more concerned over the subjective morals and ethics implicit to the text. [...] Women subjects in particular were deemed as more suitable for submissiveness, and often did not take leading roles other than as beauties [... and] were more of an anomaly generally in their discipline [across their field].[5]

Gongti which openly celebrated fleshy white beauties made up in fine outfits with their raven hair, jade ornaments and rouged makeup of the Terrace Beauty. This [the 7th] century saw instead the rise of the power wielding female, who in the tradition of Ms.Nanzi, held the real power at court.[6]

These conditions came to be with the promulgation of new power structures like the introduction of Buddhism, Male Dramatics (I call it Matriarchy) and the coming to power of Empress Wu Zetian (624-705 CE), a woman who dared to be as ruthless as her male counterparts. I deign these influential women of the period as the Rouged Meiren, a new category of elite women who achieved considerable influence in the Tang Dynasty as patrons of art, religion and wealth through marriage, commerce and active civil duty.[6] They enabled other female poets the ability to encourage the creation of the Drunken Lotus beauty, that being a beauty standard made by women from pre-existing tropes which reflected an elite female reality of life and beauty ideals which accepted the realities of womens bodies.

This saw a move towards authentic female anatomy and beauty ideals away from the Nymph Beauty ideal.[6] Women paid men like Zhou Fang (730-800) to paint their ideals and likenesses, just as Queens like Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) did to project images about their wealth, status and ergo beauty, to the world.[6] The art, including Yuefu imbued poetry genres, was imbued into contemporary ideals of beauty, demarcating beauty standards and ideals around Eastern Asia, influenced in turn by the beauty ideals of neighbouring modern India, Nepal and perhaps further afield with the affluence of the Silk Road.[6] Princess Taiping (c662 - 713CE) and her lesbian lover, Shuangguan Wan'er ( 664-710 ) carried on these traditions, undoubtedly influencing Yuefu we have now lost to time.[6]

All of these developments lead to the golden age of Chinese Arts still hailed today as the highpoint of Classical Chinese Art, the Tang Dynasty. During this era, women held great sway over politics and beauty standards, leading to the rise of the plump, comfortable Tang aristocrat who spent her days watching the moon at parties, making poetry and being decadently raunchy in and out of court. Beauty standards still followed previous epochs particularly in makeup though, with the oval face and red face dots ( 花鈿 | Hua Dian) of the Sui. Having eyebrows like Xi Shi in the Tang age for example were highly sought after, and mimicking such a great beauties personality (wink wink) and mannerisms were highly cultivated traits of a beautiful person. [...] This developed from perhaps folk ballads like Yuefu, or as Ban Zhao may have encouraged from tales like Yeh-Hsien, into the Drunken Lotus trope, where highly 'religious' women would go about their 'nun-like' ways, whilst downing many a beverage in the evening at their courts and parties listening to the latest poetry, laid out like the Queen of Sheba thinking about which male to devour next in their decadent surroundings.[6]

Yuefu influences in East Asia

These morality tales continued into the next millenium for women, who were included in Japanese poetry anthologies, as writers of literature and in their literacy and creatives of art, undoubtedly from the role Yuefu played in the Golden Age Tang poets gave to the world as its legacy. Many Japanese 'Medieval' texts from the Heian period reflect the assumptions of these Classical Yuefu structures, mostly of the late Han period in the expectations and boundaries women were expected to have occupied.

Whilst I would like to include more scholarly journals and articles on the matter, please take my word that there is very little scholarship on the matter, but that most popular beauty standards up to the Heian period stems from sex-workers like Xi-Shi and Diaochan, and that artwork has been whitewashed to erase womens roles in it's history. Traditional styles of feminine-coded art for example from this time are literally just referred to as 'Onna-E' (Womens pictures).[7] Japanese elite women for example were highly literate, creating and forging the Hiragana script when their male counterparts were studying Classical Chinese. However many of these roles are limited to that of Nun-like reclusiveness, Nikki which were to be read by very few and the roles beautiful people take in Japanese medieval literature, art and texts are all reflective of the influence of the subtle nature emphasised in the reworking of Gongti, take for example the Ashida-E (reed writing).

Onna Emakimono originated in the Heian Period when the distinction between Wamono and Kara-mono (Japanese and Chinese things) was still very fresh. These distinctions and tales were what inspired Japanese court ladies to go out and make their own cultures. Women like Ise no Miyasudokoro ( 875-938CE ), Sei Shonagon ( 966-1017CE ), Akazome Emon ( 954-1947CE ) and Murasaki Shikibu ( fl.1000-1012 ) wrote Waka, Nikkei (Diaries) and the first novel. Their aesthetic lives inspired by Six Dynasty women writers such as the bisexual Shangguan Wan'er (664-710) and instruction by Ban Zhao ( 25-117CE ) also show how they greatly admired and understood these social and cultural conventions from foreign countries, mostly China. [...] Onna-E was a culmination of Imperial court noblewomen who based on their penchant for writing literature, reading Classical Chinese and Wamono texts, created the basis for Wamono culture, pulling away from Chinese sources as was the Manly Sumi-E thing to do, and to create work tempered by Yamato-jin sensibilities. Thus Yamato-E, Otogizoshi and the Japanese school of art was born.[7]

Eventually all of these models which built upon their predecessors lead to a legacy of female art which can be seen in the influence these role models and beauties played in the creation and develop of the art of people like Iwasa Matabei and the employment of the Bijin in Ukiyo-E at the start of its inception in the 1650s in Japan and earlier with the promulgation of Classical tropes and archetypes at the hands of the Machi-Eshi and 'woman painter' of Japanese art, particularly commoner scrolls that showed a relation to Yamato-E in Emakimono.

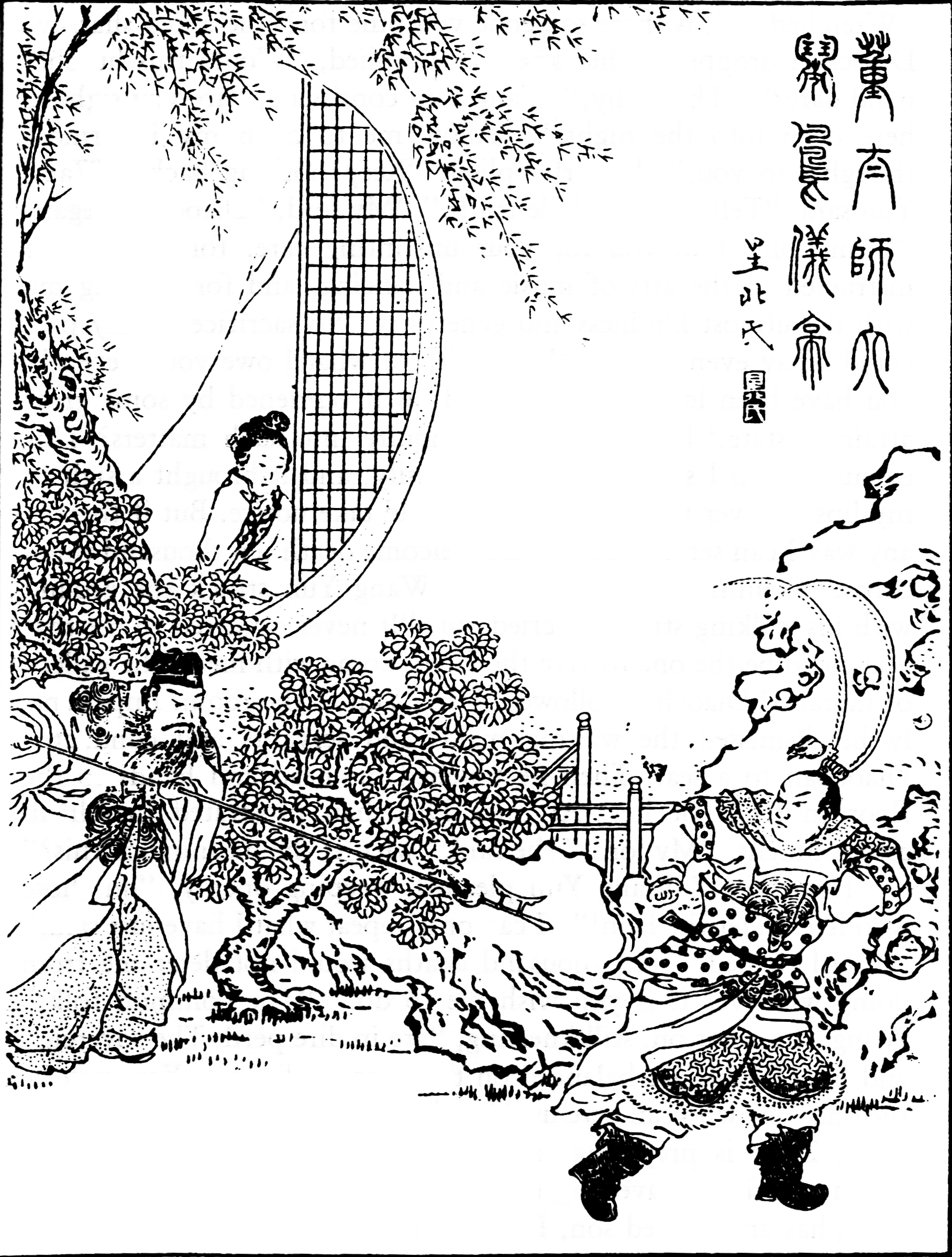

A sexy Nun (c1650, PD) Museum of Art

Tacit Beauty

All in all, Yuefu heroines reflect the push and pull (or PUSH and POPS as my linguistics degree reminds me) of the public nature female beauty has existed in and for. Yuefu reflects how women were able to take the Lotus Beauty trope to the Drunken Lotus trope in poetry, later the Arts, turning patriarchal beauty standards on their head and bringing female concerns of beauty to the fore. Yuefu proved to be a valuable medium for feminine agency and expression down the centuries, carving out a space in the 'Traditional', 'Classical' World for first the agency of women, then the empowerment of women and finally the gender expression of beauty towards the feminine spectrum. This all against the backdrop of the Voyeuristic Male Gaze into the lives of property, girls and rulers.[1][3][4]

Bibliography

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuefu

[2] See Bijin #19

[3] See Bijin #17

[4] Watching the Voyeurs: Palace Poetry and the Yuefu of Wen Tingyun, December 1989, Paul Rouzer, Volume 11, pp.13-31, CLEAR Journal | https://www.jstor.org/stable/495525

[5] See Bijin #16

[6] See Bijin #20

[7] See Essay #17

[8] See Bijin #20

Bijin Series Timeline

11th century BCE

- The Ruqun becomes a formal garment in China (1045 BCE); Ruqun Mei

8th century BCE

- Chinese clothing becomes highly hierarchical (770 BCE)

3rd century BCE

Xi Shi (flourished c201-900CE); The (Drunken) Lotus Bijin

2cnd century BCE

- The Han Dynasty

1st century BCE

Wang Zhaojun (active 38 - 31 BCE) Intermediary Bijin

0000 Current Era

1st century

- Han Tomb portraiture begins as an extension of Confucian Ancestor Worship; first Han aesthetic scholars dictate how East Asian composition and art ethics begin

- Isometric becomes the standard for East Asian Composition (c.100); Dahuting Tomb Murals

- Ban Zhao introduces Imperial Court to her Lessons for Women (c106); - Women play major roles in the powerplay of running of China consistently until 1000 CE, influencing Beauty standards

- Buddhism is introduced to China (150 CE)

- Qiyun Shengdong begins to make figures more plump and Bijin-like (c.150) but still pious

Diao Chan (192CE); The Outer Bijin

2cnd century

- Yuefu folk ballads inspire desirable beauty standards of pining women ; Tacit Bijin

4th century

Gu Kaizhi (active 364-406); Metaphorical Beauty

- Buddhism is introduced to Korea (c.372)

- Chinese Artists begin to make aesthetic beauties in ethereal religious roles of heavenly Nymphs

- Luo River Nymph Tale Scroll (c.400)

- Womens clothing emphasized the waist as the Guiyi (Swallow-Tail Flying Ribbons) style (c.400)

- Wise and Benevolent Women (c.400)

5th century

- Chinese Art becomes decadent; Imperial Culture begins to see more expression in religious statues (c450)

- Longmen Grotto Boddhisattvas (471)

6th century

Xu Ling; (active 537-583); Terrace Meiren

7th century

- Tang Dynasty Art (618-908)

- Rouged Bijin (600-699 CE) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Paintings_of_the_Tang_Dynasty

Yan Liben (active 642-673); Bodhisattva Bijin [Coming Soon] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%A1.jpg Guan Yin | https://archive.org/details/viewsfromjadeter00weid/page/22/mode/1up?view=theater

Wu Zetian (active 665-705); The Great Tang Art Patron [Coming Soon]

Asuka Bijin (c.699); The Wa Bijin

8th century

- Princess Yongtai's Veneration Murals (701) [Coming Soon]

- Introduction of Chinese Tang Dynasty clothing (710)

- Sumizuri-e (710)

Yang Yuhuan Guifei (719-756); [Coming Soon] East Asian Supermodel Bijin https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/275768522.pdf https://factsanddetails.com/china/cat2/4sub9/entry-5437.html#chapter-5

- Astana Cemetery (c.700-750) [Coming Soon]

Zhang Xuan (active 720-755); [Coming Soon]

- What is now Classical Chinese Art forms

- An Lushun Rebellion (757)

Zhou Fang (active 766-805) ; Qiyun Bijin

- Emakimono Golden Age (799-1400)

9th century

- Buddhist Bijin [Coming Soon] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Paintings_of_the_Tang_Dynasty#/media/File:Noble_Ladies_Worshiping_Buddha.jpg + https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogao_Caves#/media/File:Anonymous-Bodhisattva_Leading_the_Way.jpg

- Gongti Revival https://www.jstor.org/stable/495525?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents

10th century

-End of Tang Art (907)

13th century

- Heimin painters; 1200-1850; Town Beauty

15th century

- Fuzokuga Painting schools; Kano (1450-1868) and Tosa (1330-1690)

Tang Yin (active 1490-1524); Chinese Beauties [Coming Soon] https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/tang-yin/

16 century

- Nanbanjin Art (1550-1630)

- Wamono style begins under Chanoyu teachings (c1550-1580)

- Byobu Screens (1580-1670)

- End of Sengoku Jidai brings Stabilisation policy (1590-1615)

17th century

- Land to Currency based Economy Shift (1601-1655)

- Early Kabuki Culture (1603-1673) ; Yakusha-e or Actor Prints

- Machi-Eshi Art ( 1610 - 1710) ; The Town Beauty

- Sumptuary legislation in reaction to the wealth of the merchant classes (1604-1685)

- Regulation of export and imports of foreign trade in silk and cotton (1615-1685)

Iwasa Matabei (active 1617-1650) ; Yamato-e Bijin

The Hikone Screen (c.1624-1644) [Coming Soon]

- Sankin-Kotai (1635-1642) creates mass Urbanisation

- Popular culture and print media production moves from Kyoto to Edo (1635-1650); Kiyohara Yukinobu (1650-1682) ; Manji Classical Beauty

- Shikomi-e (1650-1670) and Kakemono-e which promote Androgynous Beauties;

Iwasa Katsushige (active 1650-1673) ; Kojin Bijin

- Mass Urbanisation instigates the rise of Chonin Cottage Industry Printing (1660-1690) ; rise of the Kabunakama Guilds and decline of the Samurai

- Kanazoshi Books (1660-1700); Koshokubon Genre (1659?-1661)

- Shunga (1660-1722); Abuna-e

Kanbun Master/School (active during 1661-1673) ; Maiko Bijin

- Hinagata Bon (1666 - 1850)

- Ukiyo Monogatari is published by Asai Ryoi (1666)

Yoshida Hanbei (active 1664-1689) ; Toned-Down Bijin

- Asobi/Suijin Dress Manuals (1660-1700)

- Ukiyo-e Art (1670-1900)

Hishikawa Moronobu (active 1672-1694) ; Wakashu Bijin

- Early Bijin-ga begin to appear as Kakemono (c.1672)

- Rise of the Komin-Chonin Relationship (1675-1725)

- The transit point from Kosode to modern Kimono (1680); Furisode, Wider Obi

- The Genroku Osaka Bijin (1680 - 1700) ; Yuezen Hiinakata

Fu Derong (active c.1675-1722) ; [Coming Soon] https://archive.org/details/viewsfromjadeter00weid/page/111/mode/1up?view=theater

Sugimura Jihei (active 1681-1703) ; Technicolour Bijin

- The Amorous Tales are published by Ihara Saikaku (1682-1687)

Hishikawa Morofusa (active 1684-1704) [Coming Soon]

- The Beginning of the Genroku Era (1688-1704)

- The rise of the Komin and Yuujo as mainstream popular culture (1688-1880)

- The consolidation of the Bijinga genre as mainstream pop culture

- The rise of the Torii school (1688-1799)

- Tan-E (1688-1710)

Miyazaki Yuzen (active 1688-1736) ; Genroku Komin and Wamono Bijin

Torii Kiyonobu (active 1688 - 1729) : Commercial Bijin

Furuyama Moromasa (active 1695-1748)

18th century

Nishikawa Sukenobu (active 1700-1750) [Coming Soon]

Kaigetsudo Ando (active 1700-1736) ; Broadstroke Bijin

Okumura Masanobu (active 1701-1764)

Kaigetsudo Doshin (active 1704-1716) [Coming Soon]

Baioken Eishun (active 1710-1755) [Coming Soon]

Kaigetsudo Anchi (active 1714-1716) [Coming Soon]

Yamazaki Joryu (active 1716-1744) [Coming Soon] | https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790976?seq=5

1717 Kyoho Reforms

Miyagawa Choshun (active 1718-1753) [Coming Soon]

Miyagawa Issho (active 1718-1780) [Coming Soon]

Nishimura Shigenaga (active 1719-1756) [Coming Soon]

Matsuno Chikanobu (active 1720-1729) [Coming Soon]

- Beni-E (1720-1743)

Torii Kiyonobu II (active 1725-1760) [Coming Soon]

- Uki-E (1735-1760)

Kawamata Tsuneyuki (active 1736-1744) [Coming Soon]

Kitao Shigemasa (1739-1820)

Miyagawa Shunsui (active from 1740-1769) [Coming Soon]

Benizuri-E (1744-1760)

Ishikawa Toyonobu (active 1745-1785) [Coming Soon]

Tsukioka Settei (active 1753-1787) [Coming Soon]

Torii Kiyonaga (active 1756-1787) [Coming Soon]

Shunsho Katsukawa (active 1760-1793) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Toyoharu (active 1763-1814) [Coming Soon]

Suzuki Harunobu (active 1764-1770) [Coming Soon]

- Nishiki-E (1765-1850)

Torii Kiyonaga (active 1765-1815) [Coming Soon]

Kitao Shigemasa (active 1765-1820) [Coming Soon]

Maruyama Okyo (active 1766-1795) [Coming Soon]

Kitagawa Utamaro (active 1770-1806) [Coming Soon]

Kubo Shunman (active 1774-1820) [Coming Soon]

Tsutaya Juzaburo (active 1774-1797) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kunimasa (active from 1780-1810) [Coming Soon]

Tanehiko Takitei (active 1783-1842) [Coming Soon]

Katsukawa Shuncho (active 1783-1795) [Coming Soon]

Choubunsai Eishi (active 1784-1829) [Coming Soon]

Eishosai Choki (active 1786-1808) [Coming Soon]

Rekisentei Eiri (active 1789-1801) [Coming Soon] [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ukiyo-e_paintings#/media/File:Rekisentei_Eiri_-_'800),_Beauty_in_a_White_Kimono',_c._1800.jpg]

Sakurai Seppo (active 1790-1824) [Coming Soon]

Chokosai Eisho (active 1792-1799) [Coming Soon]

Kunimaru Utagawa (active 1794-1829) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Toyokuni II (active 1794 - 1835) [Coming Soon]

Ryūryūkyo Shinsai (active 1799-1823) [Coming Soon]

19th century

Teisai Hokuba (active 1800-1844) [Coming Soon]

Totoya Hokkei (active 1800-1850) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kunisada Toyokuni III (active 1800-1865) [Coming Soon]

Urakusai Nagahide (active from 1804) [Coming Soon]

Kitagawa Tsukimaro (active 1804 - 1836)

Kikukawa Eizan (active 1806-1867) [Coming Soon]

Keisai Eisen (active 1808-1848) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (active 1810-1861) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Hiroshige (active 1811-1858) [Coming Soon]

Yanagawa Shigenobu (active 1818-1832) [Coming Soon]

Katsushika Oi (active 1824-1866) [Coming Soon]

Hirai Renzan (active 1838ー?) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kunisada II (active 1844-1880) [Coming Soon]

Yamada Otokawa (active 1845) [Coming Soon] | 山田音羽子 https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790976?seq=10

Toyohara Kunichika (active 1847-1900) [Coming Soon]

Kano Hogai (active 1848-1888) [Coming Soon]

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (active 1850-1892) [Coming Soon]

Noguchi Shohin (active c1860-1917) [Coming Soon]

Toyohara Chikanobu (active 1875-1912) [Coming Soon]

Uemura Shoen (active 1887-1949) [Coming Soon]

Kiyokata Kaburaki (active 1891-1972) [Coming Soon]

Goyo Hashiguchi (active 1899-1921) [Coming Soon]

20th century

Yumeji Takehisa (active 1905-1934) [Coming Soon]

Torii Kotondo (active 1915-1976) [Coming Soon]

Hisako Kajiwara (active 1918-1988) [Coming Soon] https://www.roningallery.com/artists/kajiwara-hisako | https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790976

Yamakawa Shūhō (active 1927-1944) [Coming Soon]

Social Links

One stop Link shop: https://linktr.ee/Kaguyaschest

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav

https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/

_(14781762251).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)