Ihara Saikaku, born Hirayama Tōgo (平山藤五), was a Japanese poet and creator of the "floating world" genre of Japanese prose (ukiyo-zōshi). He was the son of a wealthy merchant in Osaka, and by 1662 he became a haikai-no-renga (俳諧の連歌| linked-verse-haiku-chain) master and began to establish himself as a popular haikai poet. In 1670, he had become an established writer with his own writing style, which frequently depicted merchants or Chonin (町人|'town-people') in their natural habitat, The pleasure districts. In 1675 his wife died and he composed a hella long poem, taking 12 hours to write, written in her memory. It is said that it is this which prompted him to began writing novels. When his youngest daughter also died, he became a non-practicing-monk and began travelling around Japan. By 1677 he returned to Osaka, and hearing of the success of his 1675 poem took up writing again.

He then began writing prose fiction and he had published The Life of an Amorous Man (1682), The Great Mirror of Beauties: Son of an Amorous Man (1684), Five Women Who Loved Love (1685), The Life of an Amorous Woman (1686) and The Great Mirror of Male Love (1687) which was particularly detailed, and Comrade Loves of the Samurai (1687, Translated Collation). These later works have aged like good wine so to speak, as they were highly popular at their time of release (puns) and have remained incredibly popular among the LGBTQIA community today for their elaborative detail in Japanese history on the matter, popularised in the UK by Edward Carpenter himself (1844-1929).[1] These Erotica drew on Ihara's Chonin stories, which are said to be both satirical and comical.[2] His style was said to be so outlandish its only reference point was to the exotic 'Dutch' styles brought in by Dutch sailors into Dejima. His 1686 'Amorous Woman' novel is best remembered.[3] In 1952 it was made into the Life of Oharu.[4]

Ihara had begun upping-the-ante and created incredibly lude E compared to what had gone before in Japans historical figure art (the majority, even in Abuna-e being clothed up to this time). His accounts were mostly like saucy novellas of the lives of people from the new wealthy Chonin and their lovers, but its Osaka. His 1682 novel for instance, has the protaganist Yonosuke, who from 6-60 goes about on a island populated only by women in a bid for devoted love. These books were written to be circulated by the wider public, but the market was made due to the demand for merchant whimsy fulfillment, particularly around the pleasure district genre.[3]

As a result of his works being set amongst the Chonin, his works are both evocative of a sort of new-money beauty, which was considered rather tacky amongst the upper samurai of the time. There is indeed a lot of questionable material, but also offer a glimpse into the average kosode of the time, and some of the varied levels beauty began to take. Cheap to the rich, is not cheap to the poor as we all well know, you can only afford so many Obi before customs comes for your neck on a silver platter after all.

The kosode seen in the Sumizuri-e accompanying his 1682-1687 erotica therefore are a good indicator of what consituted the Chonins Bijin so to speak. Whilst images of finely dressed Tayuu were common to the hoi polloi as they would have been seen parading down the long avenues with their 2 child attendants and set trends, this was more of a trickle-down-economics approach. The Kosode popular in these E therefore are simpler, often using only one motif and one colour. Richer Chonin have more motifs, more colours etc but this is also due to the constraint of the sumptuary laws set by the Tokugawa Shogunates Government. This was particularly true in Osaka, a city known in Japan for its big-spenders (Japanese stereotype not mine), in the vein of Kaneo Takarada from Kill la Kill.

Ihara's Bijin in his Suzumuri-e reflected national standards and as such are reflective of the wider merchant patronage of the arts, which lead to the creation of the new textile culture in the Kansai region in the Genroku period, leading to the merchants patronage of Genroku textile culture by Osaka Genroku Nakama. This textile culture however sprang from a combination of:-

- Stabilisation policy after civil war (1590-1615)

- Sumptuary legislation in reaction to the wealth of the merchant classes (1604-1685)

- Regulation of export and imports of foreign trade in silk and cotton (1615-1685)

which merchants combated by using workarounds to create new kosode cultures through art patronage, woodblock prints and by merging old artforms together to create unique new kimono and art objects.

Sumptuous Silky and Silvery Sanctions and the rise of the Chonin (1590-1700)

Stabilisation Policy (1590-1615)

With the end of the Sengoku Jidai (戦国時代|Age of the country at war) over the Keicho period (1596-1615) came the emergence of the Sankin Kotai, when people began to move into the cities to be with their newly roving lords at first, and later to engage in the business that catered to the roving lords, with merchants owning a store in the city, and another in the countryside.[9] This was due to a policy of stabilsation and appeasement furthered by the last of the 2 unifiers of Japan, Hideyoshi Toyotomi and Ieyasu Tokugawa. Policy changes included the 1596 Hideyoshi edict which removed a large number of swords from practicing samurai in an effort to curb violent crime for example. The 1590's brought an increased trade for Kyoto Nishijin-ori silk merchants amongst these stabile trade conditions from wealthy clients.[8]

Instability however until 1615 however was rife with vigilante justice, with many Kabukimono (傾奇者|samurai gangs) & Machi-yakko (町奴|village paramilitiaries) who comprised the leftover Ronin (wandering samurai) left behind or without an overseer due to the end of Japan's many civil and local wars, which the policies aimed to regulate by creating new national workforces and systems for these displaced persons.[18] Machi Yakko contributed to the disruption of these policies by practicing non-conformity, one of their Mon crests for example combined a Kama (sickle), Wa (Circle) & the Kana phoneme for 'nu' to make Kama-wa-nu, literally "who cares", which directly questioned the political authority of sumptuary laws and the bias class structures at a time when mass hunger and infanticide were common amongst townspeople, but not amongst their ruling overlords.[11]

Sumptuary Laws (1604-1685)

Sumptuary laws simply put in England were used to dictate who could wear what colours, type of clothing, furs, fabrics, and trims from the serfs to the King. This was to establish class hierarchy, or material textile culture (so why we think Velvet is a fancy material for example, as it was Henry VIII's textile of choice) and also to regulate the English textile industry in exports and imports to bring revenue into England and to keep it out of France (a tough job as English exports were basically wool and the itchy grey broadcloth). This general idea times by about 100 applies to why the Shogunate governate regulated the Japanese textile culture and market. Whereas England has tips, Japan had R-U-L-E-S.[5] From arguably 1604-1684, new laws were put in place to try to limit the expediency of frugal Chonin. However by 1688-1720, these new Chonin had become wise to the sumptuary laws and began becoming patrons of the arts. The Chonin's spending power was vast under military policy, and and during the Kan'ei-Enpo periods (1624-1681) began to be spent on Kabuki actors and around pleasure districts. These designs quickly began to be flashier and often outshone the Kosode worn by the Bakufu (幕府|tent-government). Eventually to save face, the upper classes began to adopt these evermore expensive outfits, to keep up with the times.[9] This however became an increasingly non-option for the Bakufu who were used to living above the peasants, not borrowing from them.

Sumptuary laws stipulated things such as what fabrics and dyes could be used based upon a persons rank, decided by bloodlines at the time. The lowest of society like farmers (principally merchants though), for instance could not wear silk unless it was Tsumugi silk (waste-silk), Hemp, arrowroot, wisteria or Tilia Japonica fibres instead. The Hollyhock, Paulownia and Chrysanthemum and Beni/Murasaki dye only being allowed to be worn by nobility etc etc.[11] Merchants were later denied wearing red by the late 18th century as it was a sign of nobility and so on. This went further when considering how merchants came by their fortunes, as noble Japanese men only were allowed to make their fortunes by selling their own wares. If like merchants you sold other peoples wares, you were seen as belonging with the pondscum of society.

In Edo, merchants (Fudasashi) dealt in rice. In Osaka, these bigger merchants were the Kakeya (Moneylender) and Kuramoto (Salesman), some of whom had begun to wear the shorter sword of the samurai class, which under Confucian Buddhist Japanese standards was a no-no. Particularly to the disgruntled Tozama daimyou (outsider lords) at first. Other smaller merchants such as peddlers, entertainers and manual labourers were also gaining more wealth. Merchants in Kyoto were known for their culture, Edo for their power, and Osaka for their money. Ihara himself noted the expediency of Osaka merchants money related priorities, a pride in enterprise they held in high esteem for themselves and their wider families. This was found in self-made merchants like Kawamura Zuiken (1614-1700) who began as a cart-peddlar, and whose quick thinking after the 1657 great fire of Edo in buying local timber made him rich overnight. Edo merchants such as Kinokuniya Bunzaemon (紀伊国屋文左衛門, 1669 – 1734) were particularly known in the pleasure districts for their lavish spending.[14]

By the 1660's, Osaka Kuramoto and Kabunakama who specialised in the cash crop Cotton, instead began making domestic Kosode from Indian Sarasa prints.[8][16] The Kabunakama (株仲間|merchant guilds) began developing due to broken Nakama (contract-merchants) contracts and the cooperation and social contacts between provincial, regional and city merchants began to grow into the recognisable new flourishing Chonin class.[8][15] The Chonin according to the Chonin themselves therefore upon retirement, was to leave behind his wealth, and live a life of refinement in following Kodou, Shudo, Chado, Archery, Waka, Music, and to refrain from swearing in tripping over his purple hems.[14] In the Genroku period (1688-1704) the Chonin began to become wealthier than the Bakufu, given the Chonin dealt in coin, whereas the Japanese Warrior (read:Samurai) dealt in rice, and thereby died by the Koku-stipend.[10] Rice goes off however, so generally Chonin had a bit more leverage with accumulating wealth, from their businesses in printing, textiles, etc to meet the ratio of Supply and Demand creating in the years of population control and stabilisation policy under the new Shogunate.

Eventually the Bakufu or upper classes became evermore indebted to the Chonin or middle classes, a situation seen as untenable by the Bakufu who began issuing more stringent Sumptuary laws.[8][9] In 1683 laws were made denying lower classes from using embroidered crests and dyers could not use certain dye-processes to increase the shine or silk reflection in a kosode, and by 1684 Chonin and artisans classes were warned against using flamboyant silks and instead to wear pongee Kosode.[11] By 1685 though these Sumptuary laws directly targeted the Chonin in favour of the indebted upper classes, banning lucrative trade and displays of Confucian vulgarity; banning the merchants from flaunting their wealth in luxurious textiles.

These laws began as a Tokugawa reaction against Chonin Genroku Textile Culture.[11] But the laws in the end had little effect with textile production and culture only shifting to fit the needs of the clients.[9] As Tenka no Shonin (merchants of the nation), they held themselves now to higher callings, one of these being the elevation of the common art of clothing. Although it was more common to see Kyoto and Edo merchants spending lavish amounts, Osaka merchants were more known for their originality due to their frugality[14] leading to more cultural awareness at times than old Kyoto culture and city dwelling Edo merchants.

Osaka Genroku culture, was bold, loud, brash and in your face- the new money of entrepreneurs. In contrast for the old money, this also resulted in the pushing of the notion of Iki (being chic and reserved) by the upper classes in conformity with Confucian ideas of propriety and dress derived from Buddhist Wabi Sabi aesthetics of finding the hidden beauty in the non-material. How you dressed therefore was also a politicial statement of your background.[11]

Regulation of Foreign Trade (1615-1640)

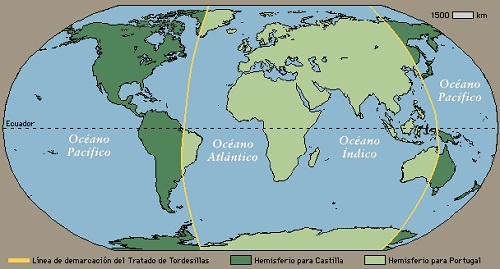

The final component of the catalyst for Genroku merchant culture was the control of foreign goods to create their luxurious textiles and goods. Foreign trade was regulated and imposed upon most heavily during the Genna period, but had its roots in the Ito-wappu Nakama system founded in 1604 which regulated which cities could import raw silk fibres into Japan.[17] With a number of extraterritorial incidents from 1595-1615 from European powers, the Bakufu became increasingly wary of foreign tradesmen and so-called-diplomats from these countries, particularly as under the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) Spain could have laid claim to Honshu, Hokkaido and Shikoku and Portugal to Kyushu.

Portugal for instance had begun converting heavily in the 1590s, bringing new technology such as the printing press from Korea and cotton from India in small amounts to Japan. It was under the Bakufu inauspicious reservations in the Genna period (1615-1624) of these powers, that Osaka Chonin beginning in 1624 had begun to become rich from the sale of textiles like Cotton and Silk, first traded with China and India.[6] It was this homegrown cotton industry created by the Genna Chonin which allowed Kosode to become a mass consumer product amongst the Chonin, and demonstrated their new middle class spending power with the Commonfolk however still dressed in local fabrics (Hemp, Linen, Ramie, and Bashofu) though to make their Kimono.[7][8]

The import of foreign textiles even extended to the Fundoshi which Chonin began making out of Indian silk.[9] Indian Chintz or Sarasa also began to be imported from Coromandel Coast, India, by the Portuguese as Sarassa which hold religious significance in certain areas of India. Most likely introduced around Nagasaki or Osaka, these printed calico fabrics being cheap to produce and brightly coloured textiles quickly became a new opportunity for Osaka merchants to make purses, Furoshiki (風呂敷|wrapping cloths) and tea related paraphenalia to attach to Kosode.[16]

Sanctions on imports against European trade was made by the Bakufu in an effort to control the outflow of silver from Japan, the English leaving Japan in 1623, the Dutch being allowed to trade only in Dejima after 1635 and the total expulsion of Iberian traders after 1639. Further consolidation of the Bakufu's sakoku policy followed, when in 1631 the Ito-wappu system was extended to Osaka to regulate the silk trade directly under the Shogunates rule.[17] From 1655-1685 this saw a level decline with the Kyoto Chonin seeing a new demand for silk after the reintroduction of Ito-wappu in 1685 saw the creation of a homegrown market around Kansai for silk, alongside the ban of Chinese imported silk to Japan in the same year.[7][8] This focused textile production in a closed national Japanese system of production creating the conditions to focus on home-made textiles.

The Genroku Osaka Bijin (1680 - 1700)

The Osaka merchants of the Genroku period became well known as the highpoint of Kabuki and pleasure district culture, promoting the arts of theatre and Asobi-dressing. It was said by the essayist Kato Eibian (1763–1829) in the 1820s, that by Genroku accounts that Osaka was 'by day a paradise, and by night as lavish as the dragon-kings palace'.[14] This lead to the proliferation of textile culture and print media, most easily summed up in the invention of the Yakusha-e (役者絵|Actor-print), one of the defining features of Ukiyo-e for print collectors today. Yakusha-e and Kabuki, and art patronage combined dramatically to transform the importance of dress, and how Kosode could and should be worn. An impetus for aesthetical dress you could say like the artistic dress of 1860-1890 in England.

Under these new conditions Kosode became ever more elaborate and ornate, reflecting popular art styles of the time. Techniques such as the Nuishime Shibori (Stitch Resist Tie-dye) were created.[9][12] Yuzen (友禅染|resist dye) from the fan-painter Miyazaki Yūzen (宮崎 友禅斎, 1654-1736), and the calligrapher Yuezen Hiinakata (dates unknown) also emerged in reaction against sumptuary laws where Kana and fan painting were applied directly to Kosode in imitation of hanging scrolls.[9][13] Kogin stitch (counted thread embroidery) was pioneered for farmers working in winter.[11] Katazome (rice paste resist dyeing) Katagami (Katazome premade-stencils) were applied by Kuramoto to Kosode to make Sarasa prints (Indian themed patterns) in floral and animal motifs.[16] Art and textile in Japan therefore became one and the same, developed through older Heian, Shinto and Buddhist aesthetic and visual traditions.

In the Kambun era (1661-1673) Kosode were generally two colours and woven with metallic thread and goldleaf. During the introduction of foreign textiles and rise of the new middle classes from the import of cotton and sarasa, tastes, colour schemes and bank balances changed. By 1684, the colour schemes of Kosode worn by the townspeople and Bakufu became darker at the bottom, lighter at the top, to show off wealth as darker Kosode meant more dye, which required deep pockets which more than often were worn by Chonin wives, well paid Kabuki performers, and the Tayuu which became 'Iki' (1680s sexy). Popular dark dyes included Beni reds (amongst samurai) / Nise-kurenai (fake/ Dutch reds for the rest) and purples.[9] A pound of Beni pigment was said to be worth a pound of gold.[11]

By 1688-1690, Yuzen dyed Kosode had become popular.[13] Uchikake also began to take on their 'furi-furi' (flapping sound) effect for young women, Kabuki performers and Asobi at this time, becoming licentious to the male population as a symbol of youth, with intricate and minute but everyday motifs like fans in ode to Buddhist humility. Regular women would simply don striped variations, or indigo Kimono which singular motifs, and both would go decorate their Kosode with wordly scenes, so scenes of the city. Bakufu wives may instead have decorated using more ethereal and abstract source material such as Genji, or the Hawks feathers to evoke classical Heian themes of love, bravery and piety.[9][11]

Chonin however set the standard for the Kosode's spatial arrangement and composition.[9] Provincial districts and merchants now set the new standard, with Osaka frequently overtaking Kyoto artwares as fashionable.[14] The Kosode of the Genroku Bijin therefore would most likely be depicted dependent upon the subject matter, but would often have use new technologies to create vivid, wordly scenery on their kosode, Onnagata and Tayuu were often seen in these styles. Younger and poorer women sticking to older Kosode fabrics such as hemp, striped cottons, linens, ramie, plant fibres or indigos with layered recycled fabrics involving the Sashiko stitch (Stab stitch).[8] They indeed often made their own Kosode, and by the middle of the 17th century weaving was a valuable skill for rural women. Richer merchants in the Genroku period would have worn deep reds, blue and purples and the closer a merchant became a samurai, the more otherwordly his garb would become, more likely to be wearing Kyoto Beni silks, than an Osaka Kuramoto's Sarasa patterned Kosode. All of this brought about new questions at the time over agency, social climbing, job security and rank throughout Japanese society as the Osaka merchants welcomed in poor and rural workers the upper classes would or did not.[11]

Ihara noted that ;-

"In everything people have a liking for finery above their station. Women’s clothes in particular go to extremes.".[11]

Therefore when we see the Bijin figures in Ihara's Suzumi-e, even in the pared down variant of Ihara who preached the 'less is more' approach himself to Kosode (given the garish, financial, illegal and dubious ethical toll of expensive dress), we can see how local cottage industries which produced recycled garments, had entered into the next epoch of faster fashion, with the inclusion of new technologies, fabrics and ideas of aesthetical acceptability fostered by the Osaka floating world and entrepreneurial merchant classes, colliding with the older more traditional notions of dress, sumptuary laws informed by Confucian ideas of propriety (which formed the notion for Iki; or Chic reservedness) amongst the Bakufu and how these were combined to make Genroku textile culture, which produced more vivid, ostentatious and elaborate layered kosode from (1630-1670), and darker garments toned down garments from (1670-1700) seen in the Suzumi-e of Ihara Saikaku in his 1680 erotica and other print media of the period which incorporated Indian, Chinese, Dutch, Portuguese and Japanese design techniques and technologies. Womens dress had become more 'furi' as Japanese society base grew to be more consumer orientated as it shifted away from feudalism, with the birth of the flamboyant or being extra Bijin, who may be austere on top, but is certainly sumptuous underneath with their flash of handpainted cheap red (the cheetah print of its day), a dynamic which defines the Kimono-Hime of today in the balancing act of understatement and flamboyance.[11]

Bibliography

[1] https://www.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.21313/hawaii/9780824866693.001.0001/upso-9780824866693-chapter-012

[2] https://endpaper60.rssing.com/chan-12330711/article379.html

[3] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ihara-Saikaku

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ihara_Saikaku

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumptuary_law [sidenote for those interested; broadcloth was frequent cause for argument among the EIC in Japan during the 1620s as it was seen as a lower form of fabric than silk when the English tried to sell it in Japan.]

[6] https://blog.patra.com/2020/09/11/history-of-japanese-silk/

[7] https://www.edo-now.com/project-05

[8] https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1605&context=tsaconf

[9] http://media.virbcdn.com/files/66/FileItem-252534-Kimono_Paper.pdf

[10] https://doctorjhwatson.wordpress.com/2015/11/18/the-koku-system/#:~:text=A%2050%2Dkoku%20stipend%20would,a%20great%20deal%20of%20strain.

[11] https://betweenthewarpandweft.wordpress.com/japanese-textiles-research-project/

[12] http://www.wodefordhall.com/page13.html

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y%C5%ABzen

[14] Merchants and Society in Tokugawa Japan, Charles Sheldon, 1983, pp.481-484, Modern Asian Studies

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabunakama

[16] https://www.kimonoboy.com/sarasa.html

[17] https://www.japanese-wiki-corpus.org/history/Itowappu.html

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabukimono

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav or https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/ or https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw, or https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/

_(BM_1979%2C0305%2C0.70.2_11).jpg)

.jpg)

_with_Cherry_Blossoms_and_Cypress_Fence_MET_1980_222.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment