The position of women in Antiquity China was highly restricted before and with the rise of Wu's rise to power. Male mediocrity at this time was highly selective, choosing patriarchy over collaboration.

Neolithic and Chalcolithic Ages

It is presumed along with wider scholarship on the global majority of workers in this age that women played a heavy part in the matrilineal work that was created during this time. Most of the work to be found in the Neolithic Chinese industry was that of artisan and craftspeople. A great amount of this was created during the 5-1 millenium BCE. These workers often took in roles such as scribes, potters and other art-workers for many of the aristocratic families which were present in the known wider elite circles. These workers as displayed in the antiquity city of Ur in modern day Iraq. These groups often worked for families whose models had equal positions which with the introduction of various abundance models (currency systems, agricultural advances, advancing writing systems) women's role increasingly became more questioned by their male equivalents.

As with Mesopotamia, as time went by these state-cities increasingly created spheres of 'women's' work. This may have started in these societies as a way to protect the mother during pregnancy, transforming into ideas of what was appropriate for women by men in the following centuries as these increasingly became limited in the role of what 'women's' work could be. 'Women's' work was increasingly demeaned, such that roles such as caring, looking after children, some art-work related roles and non-masculine affiliated roles became roles which were seen as jobs only women could, would or should perform. This is seen in the laws which increasingly constricted feminine presenting peoples gender presentation, ability to do certain jobs, to work at all, to hold property, to head a household, to vote, to go outside and to be present in rooms of importance or with men, as well as in the ownership of their own wombs, reproductive rights and children going to the father irrespective of other considerations. Women went from respected partners, to discardable property which by law had to be stoned to death if it stepped a foot wrong, whose offspring was capable of being confiscated and was perpetually to be silenced.

Femme China

We know this state of affairs from the geological record. Gravesites from this time period of the Shang Dynasty ( 5000 - 3000 BCE ) indicate that property, titles and other grave goods were passed down through women's kinship roles.[1] Other figurines found in the same time period have been found to have been representative of the divine, and used in rites which celebrated fertility, nature and religious roles.[1] It is assumed at this time, women and men were not divided into these categories, as gender was less focused on in the representative works found in gravesites and statues extant to this day, from the time.

The Majiayao culture held a number of female represented gravesites which carried a number of these statues, along with grave goods such as spindle whorls. These were small stones used in older types of looms in Ancient China to hold down threads (getting the Kimono link in there somewhere). All burials are also equally laid out with similar burial features, representative of the equality these people most likely held during their lifetimes.[1]

Patriarchal Mediocrity

The glaring perpetual absence of the feminine and the ridicule of 'feminine' attributed things is a leftover symptom of this type of violence. The silence of the historical record her speaks volumes, for the billions of women and feminine presenting individuals who were wiped from the historical record which they originally helped create, or even totally created. This patriarchal mediocrity which demanded this erasure in fear of the might, creativity and allure of the feminine lead to the complicated historical record we see today. During the late stage Neolithic period ( 2000 - 500 BCE ) the patriarchal elites of Confucian society began to pursue the Mesopotamian model of patriarchy, forcing women into increasingly restrictive modus operandi.

The gravesites of Ancient China after 2000 BCE represent a significant social status demotion for women, with women being buried away from male burials and from grave goods, as in the Qijia burial sites by 1600 BCE.[1] Some women maintained these burial rites, but this erasure would catch on with the mediocre ones for the next 2000 years.[1]

Shang

The Shang Dynasty ( 1600 BCE - 1046 BCE) was a mixed bag for feminine presenting people. 'Women' burial sites indicate elite women held political agency over their domains, owning property which was kept in their burial sites. Fu Hao ( c.1225 - 1200 BCE ) for example whilst also being connected to a male imperial court (1/64), was primarily a military general who had travelled most likely from the Steppes cultures, who fought a series of successful military ventures into neighbouring states, with 13,000 soldiers serving under her command. Fu Hao also held oracle duties (an utterly important custom at the time), owned her own domains and often used to gift the leader of the court generously. Gifts like those found in her grave site, such as human sacrifices, jade and battle-axes or from her extensive older art collection. In her death, she was buried on her own land and was invoked by the leader of the court in a spiritual bid to win battles against the Shang state.[2]

At the same time, Shang women were expected to give birth to boys and that the birth of girls was a negative event.[1] Thus the mediocre ones required to downplay any achievement a woman did as ritually less important by reducing her titles, so that they wouldn't be as butthurt.[1]

Zhou

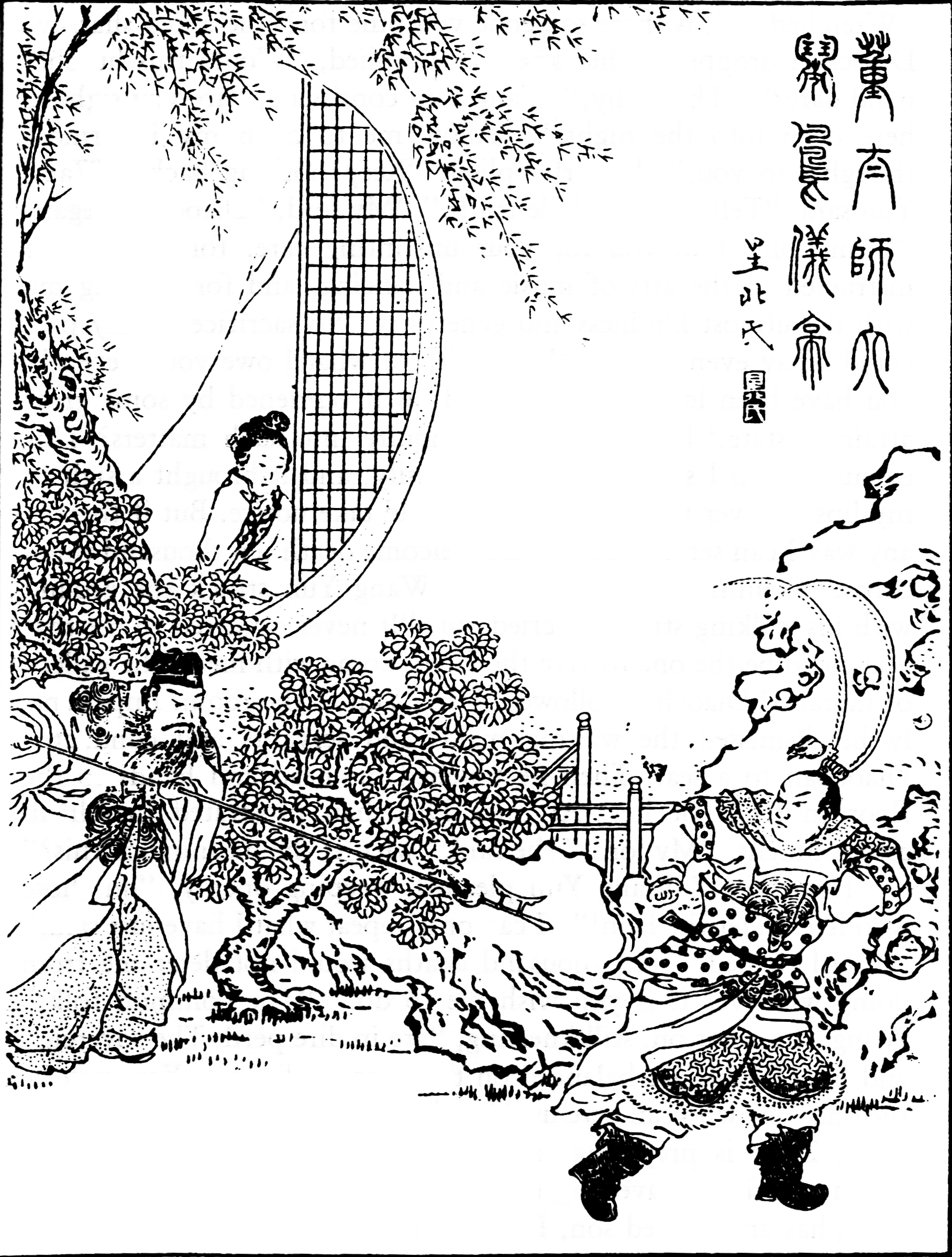

The Zhou dynasty ( 1046 BCE - 256 CE ) saw stringent changes made to feminine agency. The mediocre ones sometimes known as Confucian scholars, only made reference to male dynasties, leaders, systems of power and male role models. Women of these texts were decidedly left out. Biographies of exemplary women ( 18 BCE ) for example was written by a mediocre one, who felt it was appropriate to only some women as objects to be useful for men. Dangerous women were decidedly doing as many people as they could get their hands on, such as Diaochan (active 199-192 BCE ) who played a slightly smaller version of the game men of the time did and still do play in pitting women against each other and watching the fallout for their own personal gain.[1]

Indeed a favourite saying of the mediocre ones seems to be "men plow, women weave (男耕女織)" which essentially boils down to "big boys plow, icky cooty girls like clothes and belong in the house".[1] This created class division amongst women, leading to the creation of the upper class Jade Terrace aristocratic, and the lower class working female classes. The age of education for girls cut off at 10, an education pivoted around the Three Feminine Obediences and Four Feminine Virtues ( 三從四德 ). The 3 obediences being; 1) women must obey the father before marriage age, 2) obey the husband after marrying 3) obey her sons after the husbands death. Other fun caveats included not thinking about getting any ideas about thinking for or acting of their own free will, and also the idea that femicide should be a thing now.[1]

The first Chinese female historian and agony aunt Ban Zhao ( 49-120 CE) elaborated of The Four Virtues being 1) conduct which did not have be excellent, just to exist in the background without disturbing anyone or anything, other than the laundry pile your cheating owner creates and maintaining the beauty standards and to not have any fun play, 2) speech which must not be excellent or witty or use swear words or speak out of turn, and no laughter, lest you have an opinion of your own, 3) Comportment which must be shabby, safe and boring lest you attract male attention and lose your virginity and became a shameful Diaochan, 4) Works which do not have to be excellent or exist at all really other than laundry and weaving and hosting a mean dinner party.[3]

During this time, bride payments or dowry's were made to the male owners of women for the loss of their livestock.[1] As laid out in the mediocre work, the Six Rites.[1] Records point to this mediocrity not being followed however, as women held political ties and offices, defended themselves in law courts, practiced sports, war, conduct advice and were also literate.[1] As part of the Jade Terrace gang however, women held their own spaces in these private realms away from prying male eyes, leading to the creation of female exclusive spaces in what we call the 'Domestic Sphere' in the West by around 500 BCE - 100 CE.[1]

Qin Dynasty

During the Qin dynasty, the peasants still followed older ways such as, sending the mediocre ones to live with their wives families. This occurred commonly from 200 BCE - 200 CE.[2] At the time, patrilocal was the new mediocre control mechanism, whereas mostly prior matrilocal customs were the norm. In 214 CE mediocrity chic, a 'Purge of undesirables' became all the rage and men who got on with their wives families were purged for being 'undesirable' and made to live in non-gentrified areas to create intergenerational manurfactured poverty.[1]

Han Dynasty

Women alive during this time often went back to their own, taking charge of family affairs. Female driven marriage proposals brought money into the households at these times, in varying degrees across different states. The Han mostly not, in outer places like Steppe cultures matrilineal families were more common affairs.[1] This was following tradition which made more sense as it helped retain wealth in the women's family names. Many women often also remarried and kept on making their widow money through marital contracts, dowries and other legal methods such as land ownership. Sons of these women were often barred from office in these cases, as the mediocre ones were butthurt that women did things apparently.[1]

Widowhood was seen as the official Confucian dogmatic filial piety standard. Most normal peasants remarried however and took on more of a Diaochan type of life expounded in the Yuefu. Only the wealthier women of the Jade Terraces would not remarry and be represented in Han Tomb Murals. Women were often however painted seperate from men at this time if they were, becuase mediocrity is always butthurt. Women of this time however were often active social members, dictating wills, arranging marriages and involving themselves in the social affairs they held in the privacy of their living spaces. Upper class women owned property, land and agriculture practices which were handed down to their daughters, represented in Mural portraiture in great refinement and were increasingly represented in what became known as Outer Beauty by 100 CE, with this diminishing due to to boy drama by 250 CE.[1]

Tang Dynasty

Starting strong in 604, Emperor Yang (nobody cares | see what I did there ) altered the system so that only males could hold property and pay taxes on it.[1] However the Xianbei line of female Mongolian rulers Steppe in and start fixing the scene. This saw a more equal set of gender relations return to the ruling elites than the Han Confucian mediocre ones had allowed from the late Han to Song Dynastic periods, with women becoming more socially conscious, agentive and spiritual once again.[1] Earlier rulers included Princess Pinyang, who led 70,000 into battle, as one of the founders of the Tang Dynasty. Tang Princesses lead more active roles as diplomats, ambassadors and representatives of their states. Princess Wencheng for example introduced Buddhism to Tibet.[1] Mediocrity was curbed as male monogamy was encouraged, yet as many lovers as could be upkept were allowed.[1] Mistresses whilst still under maids were well looked after then, albeit with limited access to property upon death, often being sold to brothels upon a legal clients death, taking the brothel owners surname to work there, becoming sex workers.[1]

Wu Zetian

During this time Wu rose to power from the lower aristocratic cirlces into those of the elite. Declaring themself regnant ( 皇帝 ), Wu began the Wu-Zhou dynasty in 690 CE. Wu's successors were the dominating Empress Wei and Princess Taiping. Wu themself is said to have come from these lowly beginnings with a smattering of literacy and female only spaces of the Gongti being Wu's introduction to the feminine lead China. The Gongti circles, like that of their later Ukiyo counterparts, were freqeuntly rife with Bohemian literati writers. Wu would most likely have been aware of their contemporaries, many of whom were accomplished ladies of the night, hostesses, poets and artisans.[1] Other popular past times including become Buddhist or Taoist nuns.[1] Pilgrimages became popular at this time.[1]

Work such as Collection of New Songs from the Jade Lake were also published, by women (Cai Xengfeng) for women like Wu.[1] Chang'an became a hotbed of feminine work at this time.[1] Women were also not taxed whilst adult males were, mostly by every 20 feet of linen women wove.[1] Dress codes at the time heavily relied on ideals of traditional and modern beauty standards such as veils and cloaks, yet heavy beauty and fleshy beauty standards became popular.[1]

Mediocrity after their deaths from 700 CE onwards lead to the downfall of foreign relations and the golden age of art Wu created, leading to gems such as telling the Queen of Silla that she could not rule her own country, and women losing their veils outside.[1] The fashion for veils soon became to wear a wide brimmed hat with a gauze veil instead.[1] However other men like Emperor Dezong encouraged lady talents and scholarship, supporting the five Song sisters.[1] Examples include that of Li Ye who was summoned to court to write poetry.[1]

Song Dynasty

The mediocre ones decide lotus feet and dead women is the new beauty standard. Also popular, women remaining untouched after their owner died as their body was their husbands property, and he was gone, so therefore the body must remain untouched in a drawer somewhere like a cherished object the widow was.[1]

Conclusion

In context therefore, men can be pretty mediocre.

Bibliography

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_ancient_and_imperial_China

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fu_Hao

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Obediences_and_Four_Virtues

Bijin Series Timeline

11th century BCE

- The Ruqun becomes a formal garment in China (1045 BCE); Ruqun Mei

8th century BCE

- Chinese clothing becomes highly hierarchical (770 BCE)

3rd century BCE

Xi Shi (flourished c201-900CE); The (Drunken) Lotus Bijin

2cnd century BCE

- The Han Dynasty

1st century BCE

Wang Zhaojun (active 38 - 31 BCE) Intermediary Bijin

0000 Current Era

1st century

- Han Tomb portraiture begins as an extension of Confucian Ancestor Worship; first Han aesthetic scholars dictate how East Asian composition and art ethics begin

- Isometric becomes the standard for East Asian Composition (c.100); Dahuting Tomb Murals

- Ban Zhao introduces Imperial Court to her Lessons for Women (c106); - Women play major roles in the powerplay of running of China consistently until 1000 CE, i influencing Beauty standards

- Buddhism is introduced to China (150 CE)

- Qiyun Shengdong begins to make figures more plump and Bijin-like (c.150) but still pious

Diao Chan (192CE); The Outer Bijin

2cnd century

- Yuefu folk ballads inspire desirable beauty standards of pining women ; Tacit Bijin

4th century

Gu Kaizhi (active 364-406); Metaphorical Beauty

- Buddhism is introduced to Korea (c.372)

- Chinese Artists begin to make aesthetic beauties in ethereal religious roles of heavenly Nymphs

- Luo River Nymph Tale Scroll (c.400)

- Womens clothing emphasized the waist as the Guiyi (Swallow-Tail Flying Ribbons) style (c.400)

- Wise and Benevolent Women (c.400)

5th century

- Chinese Art becomes decadent; Imperial Culture begins to see more expression in religious statues (c450)

- Longmen Grotto Boddhisattvas (471)

6th century

Xu Ling; (active 537-583); Terrace Meiren

7th century

- Tang Dynasty Art (618-908)

- Rouged Bijin (600-699 CE) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Paintings_of_the_Tang_Dynasty

Yan Liben (active 642-673); Bodhisattva Bijin

Wu Zetian (active 665-705); The Great Tang Art Patron [Coming Fully Soon]

Asuka Bijin (c.699); The Wa Bijin

8th century

- Princess Yongtai's Veneration Murals (701) [Coming Soon]

- Introduction of Chinese Tang Dynasty clothing (710)

- Sumizuri-e (710)

Yang Yuhuan Guifei (719-756); [Coming Soon] East Asian Supermodel Bijin https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/275768522.pdf https://factsanddetails.com/china/cat2/4sub9/entry-5437.html#chapter-5

- Astana Cemetery (c.700-750) [Coming Soon]

Zhang Xuan (active 720-755); [Coming Soon]

- What is now Classical Chinese Art forms

- An Lushun Rebellion (757)

Zhou Fang (active 766-805) ; Qiyun Bijin

- Emakimono Golden Age (799-1400)

9th century

- Buddhist Bijin [Coming Soon] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Paintings_of_the_Tang_Dynasty#/media/File:Noble_Ladies_Worshiping_Buddha.jpg + https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogao_Caves#/media/File:Anonymous-Bodhisattva_Leading_the_Way.jpg

- Gongti Revival https://www.jstor.org/stable/495525?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents

10th century

-End of Tang Art (907)

13th century

- Heimin painters; 1200-1850; Town Beauty

15th century

- Fuzokuga Painting schools; Kano (1450-1868) and Tosa (1330-1690)

Tang Yin (active 1490-1524); Chinese Beauties [Coming Soon] https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/tang-yin/

16 century

- Nanbanjin Art (1550-1630)

- Wamono style begins under Chanoyu teachings (c1550-1580)

- Byobu Screens (1580-1670)

- End of Sengoku Jidai brings Stabilisation policy (1590-1615)

17th century

- Land to Currency based Economy Shift (1601-1655)

- Early Kabuki Culture (1603-1673) ; Yakusha-e or Actor Prints

- Machi-Eshi Art ( 1610 - 1710) ; The Town Beauty

- Sumptuary legislation in reaction to the wealth of the merchant classes (1604-1685)

- Regulation of export and imports of foreign trade in silk and cotton (1615-1685)

Iwasa Matabei (active 1617-1650) ; Yamato-e Bijin

The Hikone Screen (c.1624-1644) [Coming Soon]

- Sankin-Kotai (1635-1642) creates mass Urbanisation

- Popular culture and print media production moves from Kyoto to Edo (1635-1650); Kiyohara Yukinobu (1650-1682) ; Manji Classical Beauty

- Shikomi-e (1650-1670) and Kakemono-e which promote Androgynous Beauties;

Iwasa Katsushige (active 1650-1673) ; Kojin Bijin

- Mass Urbanisation instigates the rise of Chonin Cottage Industry Printing (1660-1690) ; rise of the Kabunakama Guilds and decline of the Samurai

- Kanazoshi Books (1660-1700); Koshokubon Genre (1659?-1661)

- Shunga (1660-1722); Abuna-e

Kanbun Master/School (active during 1661-1673) ; Maiko Bijin

- Hinagata Bon (1666 - 1850)

- Ukiyo Monogatari is published by Asai Ryoi (1666)

Yoshida Hanbei (active 1664-1689) ; Toned-Down Bijin

- Asobi/Suijin Dress Manuals (1660-1700)

- Ukiyo-e Art (1670-1900)

Hishikawa Moronobu (active 1672-1694) ; Wakashu Bijin

- Early Bijin-ga begin to appear as Kakemono (c.1672)

- Rise of the Komin-Chonin Relationship (1675-1725)

- The transit point from Kosode to modern Kimono (1680); Furisode, Wider Obi

- The Genroku Osaka Bijin (1680 - 1700) ; Yuezen Hiinakata

Fu Derong (active c.1675-1722) ; [Coming Soon] https://archive.org/details/viewsfromjadeter00weid/page/111/mode/1up?view=theater

Sugimura Jihei (active 1681-1703) ; Technicolour Bijin

- The Amorous Tales are published by Ihara Saikaku (1682-1687)

Hishikawa Morofusa (active 1684-1704) [Coming Soon]

- The Beginning of the Genroku Era (1688-1704)

- The rise of the Komin and Yuujo as mainstream popular culture (1688-1880)

- The consolidation of the Bijinga genre as mainstream pop culture

- The rise of the Torii school (1688-1799)

- Tan-E (1688-1710)

Miyazaki Yuzen (active 1688-1736) ; Genroku Komin and Wamono Bijin

Torii Kiyonobu (active 1688 - 1729) : Commercial Bijin

Furuyama Moromasa (active 1695-1748)

18th century

Nishikawa Sukenobu (active 1700-1750) [Coming Soon]

Kaigetsudo Ando (active 1700-1736) ; Broadstroke Bijin

Okumura Masanobu (active 1701-1764)

Kaigetsudo Doshin (active 1704-1716) [Coming Soon]

Baioken Eishun (active 1710-1755) [Coming Soon]

Kaigetsudo Anchi (active 1714-1716) [Coming Soon]

Yamazaki Joryu (active 1716-1744) [Coming Soon] | https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790976?seq=5

1717 Kyoho Reforms

Miyagawa Choshun (active 1718-1753) [Coming Soon]

Miyagawa Issho (active 1718-1780) [Coming Soon]

Nishimura Shigenaga (active 1719-1756) [Coming Soon]

Matsuno Chikanobu (active 1720-1729) [Coming Soon]

- Beni-E (1720-1743)

Torii Kiyonobu II (active 1725-1760) [Coming Soon]

- Uki-E (1735-1760)

Kawamata Tsuneyuki (active 1736-1744) [Coming Soon]

Kitao Shigemasa (1739-1820)

Miyagawa Shunsui (active from 1740-1769) [Coming Soon]

Benizuri-E (1744-1760)

Ishikawa Toyonobu (active 1745-1785) [Coming Soon]

Tsukioka Settei (active 1753-1787) [Coming Soon]

Torii Kiyonaga (active 1756-1787) [Coming Soon]

Shunsho Katsukawa (active 1760-1793) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Toyoharu (active 1763-1814) [Coming Soon]

Suzuki Harunobu (active 1764-1770) [Coming Soon]

- Nishiki-E (1765-1850)

Torii Kiyonaga (active 1765-1815) [Coming Soon]

Kitao Shigemasa (active 1765-1820) [Coming Soon]

Maruyama Okyo (active 1766-1795) [Coming Soon]

Kitagawa Utamaro (active 1770-1806) [Coming Soon]

Kubo Shunman (active 1774-1820) [Coming Soon]

Tsutaya Juzaburo (active 1774-1797) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kunimasa (active from 1780-1810) [Coming Soon]

Tanehiko Takitei (active 1783-1842) [Coming Soon]

Katsukawa Shuncho (active 1783-1795) [Coming Soon]

Choubunsai Eishi (active 1784-1829) [Coming Soon]

Eishosai Choki (active 1786-1808) [Coming Soon]

Rekisentei Eiri (active 1789-1801) [Coming Soon] [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ukiyo-e_paintings#/media/File:Rekisentei_Eiri_-_'800),_Beauty_in_a_White_Kimono',_c._1800.jpg]

Sakurai Seppo (active 1790-1824) [Coming Soon]

Chokosai Eisho (active 1792-1799) [Coming Soon]

Kunimaru Utagawa (active 1794-1829) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Toyokuni II (active 1794 - 1835) [Coming Soon]

Ryūryūkyo Shinsai (active 1799-1823) [Coming Soon]

19th century

Teisai Hokuba (active 1800-1844) [Coming Soon]

Totoya Hokkei (active 1800-1850) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kunisada Toyokuni III (active 1800-1865) [Coming Soon]

Urakusai Nagahide (active from 1804) [Coming Soon]

Kitagawa Tsukimaro (active 1804 - 1836)

Kikukawa Eizan (active 1806-1867) [Coming Soon]

Keisai Eisen (active 1808-1848) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (active 1810-1861) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Hiroshige (active 1811-1858) [Coming Soon]

Yanagawa Shigenobu (active 1818-1832) [Coming Soon]

Katsushika Oi (active 1824-1866) [Coming Soon]

Hirai Renzan (active 1838ー?) [Coming Soon]

Utagawa Kunisada II (active 1844-1880) [Coming Soon]

Yamada Otokawa (active 1845) [Coming Soon] | 山田音羽子 https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790976?seq=10

Toyohara Kunichika (active 1847-1900) [Coming Soon]

Kano Hogai (active 1848-1888) [Coming Soon]

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (active 1850-1892) [Coming Soon]

Noguchi Shohin (active c1860-1917) [Coming Soon]

Toyohara Chikanobu (active 1875-1912) [Coming Soon]

Uemura Shoen (active 1887-1949) [Coming Soon]

Kiyokata Kaburaki (active 1891-1972) [Coming Soon]

Goyo Hashiguchi (active 1899-1921) [Coming Soon]

20th century

Yumeji Takehisa (active 1905-1934) [Coming Soon]

Torii Kotondo (active 1915-1976) [Coming Soon]

Hisako Kajiwara (active 1918-1988) [Coming Soon] https://www.roningallery.com/artists/kajiwara-hisako | https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790976

Yamakawa Shūhō (active 1927-1944) [Coming Soon]

Social Links

One stop Link shop: https://linktr.ee/Kaguyaschest

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/KaguyasChest?ref=seller-platform-mcnav

https://www.instagram.com/kaguyaschest/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5APstTPbC9IExwar3ViTZw

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/LuckyMangaka/hrh-kit-of-the-suke/